|

Prolific writer, who is considered by many critics as the most important Japanese novelist of the 20th century. Mishima's works include 40 novels, poetry, essays, and modern Kabuki and Noh dramas. He was three times nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature. Among his masterpieces is The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956). The tetralogy The Sea of Fertility (1965-70) is regarded by many as Mishima's most lasting achievement. As a writer Mishima drew inspiration from pre-modern literature, both Japanese and Western. Mishima ended his brilliant literary career by suicide in 1970.

"How oddly situated a man is apt to find himself at the age of thirty-eight! His youth belongs to the distant past. Yet the period of memory beginning with the end of youth and extending to the present has left him not a single vivid impression. And therefore he persists in feeling that nothing more than a fragile barrier separates him from his youth. He is forever hearing with the utmost clarity the sounds of this neighboring domain, but there is no way to penetrate the barrier." (from Runaway Horses, 1969)

Yukio Mishima was born Kimitaka Hiraoka in Tokyo, the son of a government official. Later he changed his name into Yukio Mishima so that his anti-literary father, Azusa, wouldn't know he wrote. The name Yukio can loosely be translated as "Man who chronicals reason." On his father's side Mishima's forebears were peasants, but his ambitious grandfather eventually climbed to the position of the governor of the Japanese colony on the island of Sakhalin. Mishima's mother, Shizue Hashi, came from a family of educators and scholars.

Mishima was raised mainly by his paternal grandmother, Natsu Nagai, a cultured but unstable woman from a samurai family, who hardly allowed the boy out of her sight. During World War II Mishima was excused military service, but he served in a factory. This plagued Mishima throughout his life - he had survived shamefully when so many others had been killed. "I believe one should die young in his age," wrote Mishima's friend, the writer Hasuda, who committed suicide after the war. In February 1944, Mishima received a silver watch from Emperor Hirohito's own hand at the graduation ceremony – "he was splendid, you know, the emperor was magnificent on that day", Mishima later said.

Mishima entered in 1944 Tokyo University, where he studed law, and then worked as a civil servant in the finance ministry for eight months before devoting himself entirely to writing. Mishima's first book, Hanazakari (1944), a pastiche of decorative classical prose, appeared when he was just 19-year-old. In 1946 Mishima met Kawabata Yasunari, who recommended Mishima's stories to important magazines. His first major work, Confessions of a Mask (1949), dealt with his discovery of his own homosexuality. The narrator concludes, that he would have to wear a mask of 'normality' before other people to protect himself from social scorn. Mishima admired Oscar Wilde, of whom he published an essay in 1950.

The largely autobiographical work reflected Mishima's masochistic fantasies. His preoccupation with the body, its beauty and degeneration, marked several of his later novels. Mishima wished to create for himself a perfect body that age could not make ugly. He started body building in 1955 and he also became an expert in the martial arts of karate and kendo. Perhaps preparing for his death, Mishima liked to pose in photographs as a drowned shipwrecked sailor, St. Sebastian shot death with arrows, or a samurai committing ritual suicide. In 1960 he played a doomed yakuza, Takeo, in Yasuzo Masumura's film Karakkaze Yaro (Afraid to Die). At the end Takeo is killed, dying in a stairway. Many of Mishima's later short stories and novels delt with the theme of suicide and violent death.

''Let us remember that the central reality must be sought in the writer's work: it is what the writer chose to write, or was compelled to write, that finally matters. And certainly Mishima's carefully premeditated death is part of his work.'' (Mishima: A Vision of the Void by Marguerite Yourcenar, 1985)

AI NO KAWAKI (1950, Thirst for Love), written under the influence of the French writer François Mauriac, was a story about a woman who has become the mistress of her late husband's father.

KINKAKUJI (1956, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) was based on an actual event of 1950. It depicted the burning of the celebrated temple of Kyoto by a young Buddhist monk, who is angered at his own physical ugliness, and prevents the famous temple from falling into foreign hands during the American occupation. "My solitude grew more and more obese, like a pig." (from Temple of the Golden Pavilion)

The Sound of Waves (1954) has been filmed several times. The story, set in a remote fishing village, tells of a young fisherman, Shinji, who meets on the beach a beautiful pearl diver, Hatsue, the daughter of Miyata, the most powerful man in the village. Hatsue is loved by another young man, Yasuo. Miyata forbids Hatsue to continue seeing Shinji, but when Shinji shows his courage during a storm, he finally gives him and his daughter his blessing. The first film version from 1954, directed by Senkichi Taniguchi, was shot on location in the Shima Peninsula in Mie Prefecture, home of Japan's famous women pearl divers.

Mishima's reputation in Japan started to decline in the 1960s although in other countries his works were highly acclaimed. This decade and the next have been characterized as something of a Golden Age in the translation of Japanese fiction into English. Donald Keene, who translated several of Mishima's plays and the novel UTAGE NO ATO (1960, After the Banquet), developed a lifelong friendship with the author. KINU TO MEISATSU (1964, Silk and Insight), which John Nathan politely refused to translate (saying that the "I don't think I could make it work in English"), dealt again lost ideals, but this time the story was set in the world of silk textile manufacturing and was based on a real strike that took place in 1954, at the textile manufacturer Omi Kenshi. The central characters are an old-fashioned factory owner, Komazawa, and a manipulating political operator, Okano. Also After the Banquet, set behind the scene of politics, drew from real-life occurrences and provoked a legal suit for violating privacy.

Mishima was deeply attracted to the patriotism of imperial Japan, and samurai spirit of Japan's past. However, at the same time he dressed in Western clothes and lived in a Western-style house.

In 1968 he founded the Shield Society (Tate no Kai), a private army of some 100 youths in uniforms worked on de Gaulle's uniform, who were dedicated to a revival of Bushido, the samurai knightly code of honour. In 1970 he seized control in military headquarters in Tokyo, trying to rouse the nation to pre-war nationalist heroic ideals. His coup d'état was doomed from the beginninbg.

On November 25, after failure, Mishima committed seppuku (ritual disembowelment) with his sword within the compounds of the Ground Self-Defense Force. Before he died he shouted, ''Long live the Emperor.'' As he fell on the carpet, he was beheaded by one of his men, acting as a kaishaku, the one who delivers the decapitating sword-blow. After his death, Mishima's wife had the negative of Patriotism (1966) burned, a film in which Mishima played the leading role and committed suicide at the end.

On the day of his death Mishima delivered to his publishers the final pages ofTennin Gosui (The Sea of Fertility), the authors account of the Japanese experience in the 20th century. Mishima based the theme on the Buddhist idea of the transmigration of the soul. The first part of the four-volume novel, Spring Snow(1968), is set in the closed circles of Tokyo's Imperial Court in 1912. It was followed by Runaway Horses (1969), The Temple of Dawn (1970) and Five Signs of a God's Decay (1971). Each of the novels depict a different reincarnation of the same being, Honda, who dies at the age of twenty: first as a young aristocrat, then as a political fanatic in the 1930s, as a Thai princess before and after World War II, and as an evil young orphan in the 1960s. The tennin in the tetralogy's Japanese title refers to a supernatural being Buddhist theology, who has similarities with the Christian angel but who is mortal.

"Just let matters slide. How much better to accept each sweet drop of the honey that was Time, than to stoop to the vulgarity latent in every decision. However grave the matter at hand might be, if one neglected it for long enough, the act of neglect itself would begin to affect the situation, and someone else would emerge as an ally. Such was Count Ayakura's version of political theory." (From Spring Snow, 1968)

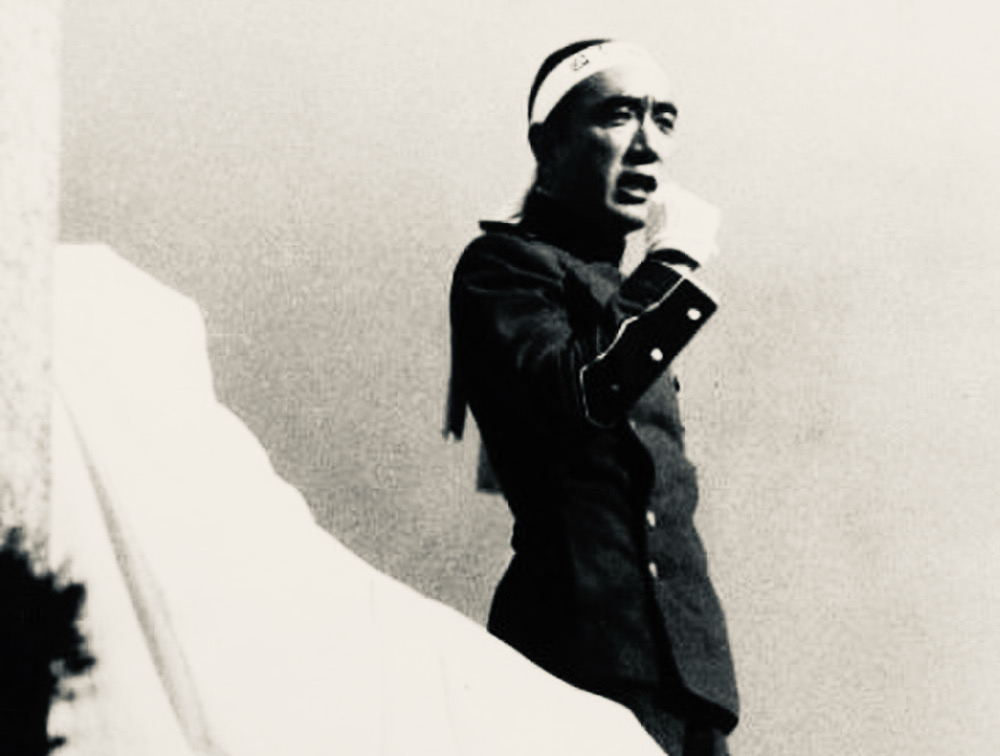

On November 25, 1970 Yukio Mishima stood on a balcony in front of some one thousand servicemen at the Tokyo command of the Eastern Headquarters of Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Forces, and exhorted them to rise up against Japan’s postwar Constitution, which prohibits the country from having an army and forbids war. He then turned back to the room where he and four followers had barricaded themselves and proceeded to perform harakiri, ritual Japanese suicide. This involved driving a razor-sharp Japanese sword into his stomach and then having his head sliced off by a waiting friend. On the day of his death Mishima had delivered to his publishers the final pages ofTennin Gosui (The Sea of Fertility), the author’s account of the Japanese experience in the twentieth century.

Mishima’s aesthetic ideal was the beauty of a violent death in one’s prime, an ideal common in classical Japanese literature. As a sickly youngster, Mishima’s ideal of the heroic death had already taken hold: “A sensuous craving for such things as the destiny of soldiers, the tragic nature of their calling . . . the ways they would die.”

He was determined to overcome his physical weaknesses. There is much of the Nietzschean “Higher Man” about him, of overcoming personal and social restraints to express his own heroic individuality.

His motto was: “Be Strong.”

World War II had a formative influence on Mishima. Along with his fellow students, he felt that conscription and certain death waited.[14] He became chairman of the college literary club, and his patriotic poems were published in the student magazine.[15] He also co-founded his own journal and began to read the Japanese classics, becoming associated with the nationalistic literary group Bungei Bu, that believed war to be holy.

However, Mishima barely passed the medical examination for military training. He was drafted into an aircraft factory where kamikaze planes were manufactured.

In 1944, he had his first book, Hanazakan no Mori (The Forest in Full Bloom) published, a considerable feat in the final year of the war, which brought him instant recognition.

While Mishima’s role in the war effort was obviously not as he would have wished, he spent the rest of his life in the post-war world attempting to fulfill his ideals of Tradition and the Samurai ethic, seeking to return Japan to what he regarded as its true character amidst the democratic era in which the ideal of “peace” is an unquestioned absolute (even though it has to be continually enforced with much military spending and localized wars).

In 1966, Mishima wrote: “The goal of my life was to acquire all the various attributes of the warrior.” His ethos was that of the Samurai Bunburyodo-ryodo: the way of literature (Bun) and the Sword (Bu), which he sought to cultivate in equal measure, a blend of “art and action.” “But my heart’s yearning towards Death and Night and Blood would not be denied.” His ill-health as a youth had robbed him of what he clearly viewed as his true destiny: to have died during the War in the service of the Emperor, like so many other young Japanese. He expressed the Samurai ethos: “To keep death in mind from day to day, to focus each moment upon, inevitable death . . . the beautiful death that had earlier eluded me had also become possible. I was beginning to dream of my capabilities as a fighting man.”

In 1966, Mishima applied for permission to train at army camps, and the following year wrote Runaway Horses, the plot of which involves Isao, a radical Rightist student and martial arts practitioner, who commits hara-kiri after fatally stabbing a businessman Isao had been inspired by the book Shinpuren Shiwa (“The History of Shinpuren”) which recounts the Shinpuren Incident of 1877, the last stand of the Samurai when, armed only with spears and swords, they attacked an army barracks in defiance of Government decrees prohibiting the carrying of swords in public and ordering the cutting off of the Samurai topknots. All but one of the Samurai survivors committed hara-kiri. Again Mishima was using literature to plot out how he envisaged his own life unfolding and ending, against the backdrop of tradition and history.

“A samurai is a total human being, whereas a man who is completely absorbed in his technical skill has degenerated into a ‘function’, one cog in a machine.” The Feminization of Society

One of the primary themes of interest for the present-day Western reader of Mishima’s commentary on Hagakure is Mishima’s use of Jocho’s observations on his own epoch to analyze the modern era. Both seventeenth century Japan and twentieth century Japan manifest analogous symptoms of decadence, the latter due to the imposition of alien values that are products of the West’s cycle of decay, while those of Jocho’s day indicate that Japanese civilization in his time was in a phase of decay. Therefore, those interested in cultural morphology, Spengler’s in particular, will see analogues to the present decline of Western civilization in Jocho’s analysis of his time and Mishima’s analysis of post-war Japan.

The first symptom considered by Mishima is the obsession of youth with fashion. Jocho observed that even among the Samurai, the young talked only of money, clothes, and sex, an obsession that Mishima observed in his time as well.

Mishima also pointed out that the post-war feminization of the Japanese male was noted by Jocho during the peaceful years of the Tokugawa era. Eighteenth-century prints of couples hardly distinguish between male and female, with similar hairstyles, clothes, and facial expressions, which make it impossible to tell who is the male and who the female. Jocho records in Hagakure that during his time, the pulse rates of men and women, which usually differ, had become the same, and this was noted when treating medical ailments. He called this “the female pulse.”[41] Jocho observed: “The world is indeed entering a degenerate stage; men are losing their virility and are becoming just like women . . .”

Celebrities Replace Heroes

Jocho condemns the idolization of certain individuals achieving what we’d today call celebrity status. Mishima comments:Today, baseball players and television stars are lionized. Those who specialize in skills that will fascinate an audience tend to abandon their existence as total human personalities and be reduced to a kind of skilled puppet. This tendency reflects the ideals of our time. On this point there is no difference between performers and technicians.

Intellectualism

Mishima held intellectuals in the same contempt as Westerners who were also in revolt against the modern world, such as D. H. Lawrence, who believed that the life force or élan vital is repressed by rationalism and intellectualism and replaced by the counting house mentality of the merchant, not just in business but in all aspects of life. Jocho stated that:The calculating man is a coward. I say this because calculations have to do with profit and loss, and such a person is therefore preoccupied with profit and loss. To die is a loss, to live is a gain, and so one decides not to die. Therefore one is a coward. Similarly a man of education camouflages with his intellect and eloquence the cowardice or greed that is his true nature. Many people do not realize this.

Mishima comments that in Jocho’s time there was probably nothing corresponding to the modem intelligentsia. However, there were scholars, and even the Samurai themselves had begun to form themselves into a similar class “in an age of extended peace.” Mishima identifies this intellectualism with “humanism,” as did Spengler. This intellectualism means, contrary to the Samurai ethic, that “one does not offer oneself up bravely in the face of danger.”

The law

“The law is an accumulation of tireless attempts to block a man’s desire to change life into an instant of poetry. Certainly it would not be right to let everybody exchange his life for a line of poetry written in a splash of blood. But the mass of men, lacking valor, pass away their lives without ever feeling the least touch of such a desire. The law, therefore, of its very nature is aimed at a tiny minority of mankind.”

Cult of the Hero – A Mighty Nihilism

“Facile cynicism, invariably, is related to feeble muscles or obesity, while the cult of the hero and a mighty nihilism are always are always related to a mighty body and well-tempered muscles. For the cult of the hero is, ultimately, the basic principle of the body, and in the long run is intimately involved with the contrast between the robustness of the body and the destruction that is death.”

On Art

“…there is no discipline so easy to speak of and so difficult to perform as the Combined Way of the Warrior and the Scholar. I decided that nothing else could offer me the excuse to live my life as an artist. This realization, too, I owe to Hagakure.”

On Women

Women can bring nothing into the world but children. Men can father all kinds of things besides children. Creation, reproduction, and propagation are all male capabilities. Feminine pregnancy is but a part of child rearing. This is an old truth.Women’s jealousy is simple jealousy of creativity. A woman who bears a son and brings him up tastes the honeyed joy of revenge against creativity. When she stands in the way of creation she feels she has something to live for. The craving for luxury and spending is a destructive craving. Everywhere you look, feminine instincts win out. Originally capitalism was a male theory, a reproductive theory. Then feminine thinking ate away at it. Capitalism changed into a theory of extravagance. Thanks to this Helen, war finally came into being. In the far distant future, communism too will be destroyed by woman. Woman survives everywhere and rules like the night. Her nature is on the highest pinnacle of baseness. She drags all values down into the slough of sentiment. She is entirely incapable of comprehending doctrine: ‘-istic’, she can understand; ‘-ism’, she cannot fathom. Lacking in originality she can’t even comprehend the atmosphere. All she can figure out is the smell. She smells as a pig does. Perfume is a masculine invention designed to improve woman’s sense of smell. Thanks to it, man escapes being sniffed out by woman. Woman’s sexual charm, her coquettish instincts, all the powers of her sexual attraction, prove that woman is a useless creature. Something useful would have no need of coquetries. What a waste it is that man insists on being attracted by woman! What disgrace it brings down upon man’s spiritual powers! Woman has no soul; she can only feel. What is called majestic feeling is the most laughable of paradoxes, a self-made tapeworm. The majesty of motherhood that once in a while develops and shocks people has no truth in relation to spirit. It is no more than a physiological phenomenon, essentially no different from the self-sacrificing mother love seen in animals. In short, spirit must be viewed as the special characteristic that differentiates man from the animals. It is the only essential difference.

Mishima committed ritual suicide on November 25, 1970. Below are his last words. It is not the complete text but relevant excerpts.

CONDEMNATION OF POST WORLD WAR II JAPAN We have watched as postwar Japan has become infatuated with economic prosperity and forgotten the foundational principles of the nation. Citizens have lost their solidarity, rush ahead without correcting fundamental problems, have fallen into stopgap measures and hypocrisy, and have cast their own souls into a state of emptiness. Politics is just a facade over a mass of contradictions, self-preservation, lust for power and hypocrisy. Any long-term plans for the nation a hundred years from now have been consigned to foreign countries. We have watched with gritted teeth as the the shame of defeat has been ducked and avoided rather than wiped away, and as Japanese themselves sully their own history and traditions.

MISHIMA SEES MILITARY AS HOPE OF JAPAN TODAY Even now we dream of the SDF as the only place where the true Japan, true Japanese, and the true soul of the warrior remains. Furthermore, it is clear that legally the SDF is unconstitutional. The fundamental issue of the nation’s defense has been weaseled around with an opportunistic legal interpretation, and we have seen how having a military that does not use the name “military” has become the source of corruption of Japanese souls and the degeneration of morality. The military, which should hold the loftiest honor, has been subject to the basest of deceits. The SDF continues to bear the dishonorable cross of a defeated nation. The SDF is not a national military, has not been accorded the foundational principles of a military, has only been given the status of a physically large police force, and even the target of its loyalty has not been made clear. Postwar Japan’s long slumber enrages us. We believe that the moment the SDF awakens will be the same moment Japan awakens. And we believe that if the SDF does not awaken itself, Japan will also fail to awaken. And we believe that our greatest duty as citizens is to exert all our effort, however feeble, to work towards the day when, through constitutional reform, the SDF can be made into a true national military and stand upon a military’s foundational principle. Four years ago I entered the SDF alone with this ambition, the next year I formed the Shield Society. The fundamental principle of the Shield Society is the resolve to sacrifice our lives so that the SDF might awaken, to make it into a national military, a national military with honor. Since constitutional reform was already difficult under the parliamentary system, a domestic security operation* offered our only chance. So we aimed to cast aside our lives as the vanguard of a domestic security operation and become the keystone of the national military. A military protects its nation, a government is defended by the police. When we arrive at the stage where the government can no longer be effectively defended by the police, a deployment of the military will make it clear just what the nation is, and the military will revive its foundational principle. The foundational principle of a Japanese military can only be “protecting Japanese history, culture and tradition centered on the emperor.” In order to correct the twisted foundation of this nation, we, though few in number, trained ourselves and volunteered ourselves to this task. Ever since that day, we have been watching the SDF carefully, moment by moment. If, as we had dreamed, the soul of the warrior still remained in the SDF, how could it ignore this situation? Protecting the very thing that negated it, surely that is a logical contradiction. If you are men, how could a man’s pride allow this? Even after enduring and enduring, rising up with firm resolution once the last line of what you are supposed to protect has been crossed is what it means to be a man, what it means to be a warrior. We desperately strained our ears. But from nowhere in the SDF did we hear a man’s voice rise in response to the humiliating order to “protect that which negates you.” Now that it has come to this, with the awareness of your own power, you knew that the only path forward was the correction of the twisted logic of the nation, but the SDF has been as silent as a canary with its voice stolen. We were sad, angry, and finally enraged. Gentlemen, can you do nothing without being given a mission? But, sadly, the mission accorded to you will ultimately not come from Japan. It is said that civilian control is the basic principle of a democratic military. However, in England and America civilian control means financial control over military administration. Unlike Japan, it does not mean that the military is castrated without even the right to make personnel decisions, manipulated by treacherous politicians, or used as a pawn in partisan politics.

CONDEMNATION OF CURRENT JAPANESE MILITARY Furthermore, it seems the SDF has swallowed the flattery of politicians and is walking the path of even deeper self-deceit and self-desecration. Where has the soul of the warrior gone? How will you go on, as nothing but a giant armory whose soul is dead? During textile negotiations, textile workers called the LDP traitors. Yet although it is clear that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which concerns the long-term security of the nation, is the rebirth of the 5:5:3 Unequal Treaty, not one general from the SDF has cut his stomach in protest. What does the return of Okinawa mean? What does the defense of the mainland mean? It is clear that America doesn’t want Japanese territory being defended by a true autonomous Japanese military. If we can’t revive our autonomy within the next two years, the SDF will end forever as, in the left-wing’s words, mercenaries for America.

ANNOUNCEMENT OF RITUAL SUICIDE TO INSPIRE REVOLUTION We waited four years. The last year we waited with particular passion. We can wait no longer. We cannot wait for those who would desecrate themselves. But another thirty minutes; let us wait the final thirty minutes. We rose up together and together we will die for righteousness. To return Japan to Japan’s true form, that is why we die. Is it enough to insist on the sanctity of life, even when the soul is dead? What sort of military holds nothing above the value of life? Gentlemen, we are now going to show you a value even greater than the sanctity of life. That is not freedom, nor democracy. It is Japan. The country of history and tradition that we love, Japan. Is there no one here who will throw their bodies against this degenerate constitution and die? If there is, stand with us and die with us now. We have undertaken this action in the fervent hope that you, gentlemen, who have the purest of souls, may be reborn as individual men and as warriors.

|

.jpg)