NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

Hope

Links

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Persona (1966)

“Persona” is a film we return to over the years, for the beauty of its images and because we hope to understand its mysteries.

Visually stunning and displaying more intense close-ups than probably any other film we’ve seen, the film was shot by Bergman’s frequent partner, the celebrated Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist. The shot of Andersson and Ullmann’s face joined together, the startling sequence of the image breaking apart in the middle of the film and the beautiful dichotomy between light and dark echoing the same relationship between silence and voice is Bergman and Nykvist’s visual triumph that is forever etched in our memory. With famous opera composer Lars Johan Werle’s score and Ulla Ryghe editing skills, Persona is a work of technical mastery, while Andersson and Ullmann delivered on what Bergman expected from them to the degree of critics claiming the film rested on their inspired shoulders. Persona is still a delight to watch, a visionary, influential, highly contemplative work of art that hasn’t aged a day

Shakespeare used six words to pose the essential human choice: “To be, or not to be?” Elizabeth, a character in Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona,” uses two to answer it: “No, don’t!” She is an actress who one night stopped speaking in the middle of the performance, and has been silent ever since. Now her nurse, Alma, has in a fit of rage started to throw a pot of boiling water at her. “No, don’t!” translates as: I do not want to feel pain, I do not want to be scarred, I do not want to die. She wants . . . to be. She admits . . . she exists.

“Persona” (1966) is a film we return to over the years, for the beauty of its images and because we hope to understand its mysteries. It is apparently not a difficult film: Everything that happens is perfectly clear, and even the dream sequences are clear–as dreams. But it suggests buried truths, and we despair of finding them. “Persona” was one of the first movies I reviewed, in 1967. I did not think I understood it. A third of a century later I know most of what I am ever likely to know about films, and I think I understand that the best approach to “Persona” is a literal one.

- Release date: March 16, 1967 (USA)Director: Ingmar BergmanCinematography: Sven NykvistScreenplay: Ingmar BergmanRunning time: 1h 23mLanguage: Swedish

- Release date: March 16, 1967 (USA)Director: Ingmar BergmanCinematography: Sven NykvistScreenplay: Ingmar BergmanRunning time: 1h 23mLanguage: Swedish

INGMAR BERMAN ON ‘PERSONA’

“It is a tremendously irrational process that appears different every time. The core of the films, the originally explosive material, creates the film; the final film can consist of perhaps apparently strangely unimportant impulses. The idea for Persona, for example, came from a picture. One day I suddenly saw in front of me two women sitting next to each other and comparing hands with one another. I thought to myself that one of them is mute and the other one speaks. This little thought returned time and again and I wondered: why did it return, why did it repeat itself? It was as if it returned so that I would start to work on it. And then you realize that there is something behind this picture, it is as if it was on a door. And if you open the door carefully, there is a long corridor that becomes broader and broader and you suddenly see scenes that act themselves out and people who start to speak and situations that start to develop themselves on both sides.

But I think this is true of all artisticness. Film may be specially visual. For me, it goes on to develop itself in rhythm and in light. If I return to the picture in Persona, light broke down through the hats (they wore sort of basket hats) and over the girls’ faces. The sun was strong in this picture. It’s very strange, but the light is an integrated part of my first experience. It is often awfully concrete pictures and some sort of acoustic sensation. Other ideas can grow out of a dream or a piece of music, a few strokes of a piece of music. The Silence, for example, grew out of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra. Winter Light grew out of Stravinsky’s Psalm Symphony. I don’t know how, but sometimes music creates a tension, a situation.” —Ingmar Bergman

“It is a tremendously irrational process that appears different every time. The core of the films, the originally explosive material, creates the film; the final film can consist of perhaps apparently strangely unimportant impulses. The idea for Persona, for example, came from a picture. One day I suddenly saw in front of me two women sitting next to each other and comparing hands with one another. I thought to myself that one of them is mute and the other one speaks. This little thought returned time and again and I wondered: why did it return, why did it repeat itself? It was as if it returned so that I would start to work on it. And then you realize that there is something behind this picture, it is as if it was on a door. And if you open the door carefully, there is a long corridor that becomes broader and broader and you suddenly see scenes that act themselves out and people who start to speak and situations that start to develop themselves on both sides.

But I think this is true of all artisticness. Film may be specially visual. For me, it goes on to develop itself in rhythm and in light. If I return to the picture in Persona, light broke down through the hats (they wore sort of basket hats) and over the girls’ faces. The sun was strong in this picture. It’s very strange, but the light is an integrated part of my first experience. It is often awfully concrete pictures and some sort of acoustic sensation. Other ideas can grow out of a dream or a piece of music, a few strokes of a piece of music. The Silence, for example, grew out of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra. Winter Light grew out of Stravinsky’s Psalm Symphony. I don’t know how, but sometimes music creates a tension, a situation.” —Ingmar Bergman

Bergman, Ingmar

FILMING—PART I

Shows Bergman’s directing style as Gunnar Björnstrand and Ingrid Thulin are guided through a key scene in the film (in an essay included with the disc, Sjöman reveals that this episode is an “arranged rehearsal,” made several days after the real shooting for the scene had been done).

Shows Bergman’s directing style as Gunnar Björnstrand and Ingrid Thulin are guided through a key scene in the film (in an essay included with the disc, Sjöman reveals that this episode is an “arranged rehearsal,” made several days after the real shooting for the scene had been done).

FILMING—PART II

An on-set interview of Bergman by Sjöman about his directing philosophy, strengths and weaknesses.

An on-set interview of Bergman by Sjöman about his directing philosophy, strengths and weaknesses.

POSTPRODUCTION

Goes step-by-step through the editing of one scene from the raw footage through the final edit. It also covers the sound mixing.

Goes step-by-step through the editing of one scene from the raw footage through the final edit. It also covers the sound mixing.

THE PREMIERE

Shows the planning of the film’s release, both in Sweden and internationally; interviews audience members and critics about their reaction to the film.

Shows the planning of the film’s release, both in Sweden and internationally; interviews audience members and critics about their reaction to the film.

‘Persona’: Ingmar Bergman’s Psychological Masterpiece as the White Whale of Critical Analysis >>> (Full Cinephila & Beyond)

By Sven Mikulec

In 1963 Ingmar Bergman was appointed head of the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm. Refusing to cut back on his filmmaking projects, exhausted and stressed out, he soon fell ill. In his nine weeks of recovery from a rather difficult case of pneumonia accompanied by acute penicillin poisoning, trying to keep his mind occupied, Bergman developed an idea for a new film—the groundbreaking and analytically elusive Persona, today hailed as one of the most significant and accomplished films of the 20th century. Having all the time in the world to contemplate his work, filmmaking and art in general, he came up with a story centered on duality, loneliness, insanity, personal identity and the theme of representation. The crucial image on which he based his vision came to him as he saw a slide of actresses Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann sunbathing together, with a resemblance he deemed uncanny. Andersson was his long-time collaborator, but Ullmann was a complete mystery to him. One brief chance encounter on the street, however, put his mind at ease. He was convinced he found two perfect matches for the main parts in the film. Having contacted filmmaker Kenne Fant, then CEO of the Swedish Film Industry, Bergman asked if he would fund his next project, after which Fant wanted to know more about the film’s plot. “Well, it’s about one person who speaks and one who doesn’t, and they compare hands and get all mingled up in one another,” Bergman responded. Assuming such a film simply couldn’t cost a lot of money, Fant agreed and the project was on its way.

Shot during two months of the summer of 1965, Persona had a rough start, as almost nothing went according to plan when the production took place at the Filmstaden studio in Stockholm, but as soon as the crew moved to the island of Fårö, where Bergman would later frequently go to charge his creative batteries, the production somehow took off. Upon its release, most critics were respectful, acknowledging the obvious craft that went into the creation of the film, but almost all of them agreed the film was a real challenge to decipher, resisting unanimous analysis and simple categorization. Persona is definitely among only a handful of films to receive such extensive analytical treatment by critics and scholars, who saw it as their white whale. A part of the beauty of this film, in fact, lies in this very quality: Persona can’t be stripped down to a single, unambiguous truth, something that Bergman himself understood all too well. “On many points I am unsure, and in one instance, at least, I know nothing,” he stated when asked what the exact theme and message of the film really was.

Visually stunning and displaying more intense close-ups than probably any other film we’ve seen, the film was shot by Bergman’s frequent partner, the celebrated Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist. The shot of Andersson and Ullmann’s face joined together, the startling sequence of the image breaking apart in the middle of the film and the beautiful dichotomy between light and dark echoing the same relationship between silence and voice is Bergman and Nykvist’s visual triumph that is forever etched in our memory. With famous opera composer Lars Johan Werle’s score and Ulla Ryghe editing skills, Persona is a work of technical mastery, while Andersson and Ullmann delivered on what Bergman expected from them to the degree of critics claiming the film rested on their inspired shoulders. Persona is still a delight to watch, a visionary, influential, highly contemplative work of art that hasn’t aged a day

By Sven Mikulec

In 1963 Ingmar Bergman was appointed head of the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm. Refusing to cut back on his filmmaking projects, exhausted and stressed out, he soon fell ill. In his nine weeks of recovery from a rather difficult case of pneumonia accompanied by acute penicillin poisoning, trying to keep his mind occupied, Bergman developed an idea for a new film—the groundbreaking and analytically elusive Persona, today hailed as one of the most significant and accomplished films of the 20th century. Having all the time in the world to contemplate his work, filmmaking and art in general, he came up with a story centered on duality, loneliness, insanity, personal identity and the theme of representation. The crucial image on which he based his vision came to him as he saw a slide of actresses Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann sunbathing together, with a resemblance he deemed uncanny. Andersson was his long-time collaborator, but Ullmann was a complete mystery to him. One brief chance encounter on the street, however, put his mind at ease. He was convinced he found two perfect matches for the main parts in the film. Having contacted filmmaker Kenne Fant, then CEO of the Swedish Film Industry, Bergman asked if he would fund his next project, after which Fant wanted to know more about the film’s plot. “Well, it’s about one person who speaks and one who doesn’t, and they compare hands and get all mingled up in one another,” Bergman responded. Assuming such a film simply couldn’t cost a lot of money, Fant agreed and the project was on its way.

Shot during two months of the summer of 1965, Persona had a rough start, as almost nothing went according to plan when the production took place at the Filmstaden studio in Stockholm, but as soon as the crew moved to the island of Fårö, where Bergman would later frequently go to charge his creative batteries, the production somehow took off. Upon its release, most critics were respectful, acknowledging the obvious craft that went into the creation of the film, but almost all of them agreed the film was a real challenge to decipher, resisting unanimous analysis and simple categorization. Persona is definitely among only a handful of films to receive such extensive analytical treatment by critics and scholars, who saw it as their white whale. A part of the beauty of this film, in fact, lies in this very quality: Persona can’t be stripped down to a single, unambiguous truth, something that Bergman himself understood all too well. “On many points I am unsure, and in one instance, at least, I know nothing,” he stated when asked what the exact theme and message of the film really was.

Visually stunning and displaying more intense close-ups than probably any other film we’ve seen, the film was shot by Bergman’s frequent partner, the celebrated Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist. The shot of Andersson and Ullmann’s face joined together, the startling sequence of the image breaking apart in the middle of the film and the beautiful dichotomy between light and dark echoing the same relationship between silence and voice is Bergman and Nykvist’s visual triumph that is forever etched in our memory. With famous opera composer Lars Johan Werle’s score and Ulla Ryghe editing skills, Persona is a work of technical mastery, while Andersson and Ullmann delivered on what Bergman expected from them to the degree of critics claiming the film rested on their inspired shoulders. Persona is still a delight to watch, a visionary, influential, highly contemplative work of art that hasn’t aged a day

“I’ve really managed to make a film that has sparked a debate it would be very tactless of me to barge in on that debate and talk about what I really meant by the film. It would be tactless toward the audience, because I’m sure they all have their own interpretations, and tactless towards those commenting on it in the media, who might feel hurt if they found they’d misinterpreted the film. Therefore I prefer not to say anything at all. I played my part in this debate when I made the film.” —Ingmar Bergman

“One can say that film direction is the transformation of visions, ideas, dreams, and hopes into pictures that are to convey these feelings to the audiences in the most efficient manner. One creates some sort of medium, this long strip of film that reproduces one’s dreams through a lot of machines. Pictures to the feelings of others, to other people. One can also say that film direction can be given a technical definition. Along with an awful lot of people, performers, and technicians, and a tremendous lot of machines, one produces a product. It’s an everyday product or a work of art, whichever one prefers.” —Ingmar Bergman

Ingmar Bergman: The Serpent’s Skin, Cahiers du Cinéma in English #11, September 1967

Conversation with Bibi Andersson on Ingmar Bergman’s latest film, Persona, and on the influence that this director, with which she shot eight films, has had on her. Broadcast date: 19 May, 1966.

At the end of Persona, mask and person, speech and silence, actor and ‘soul’ remain divided—however parasitically, even vampiristically, they are shown to be intertwined. —‘Persona’ by Susan Sontag, Sight and Sound, autumn 1967

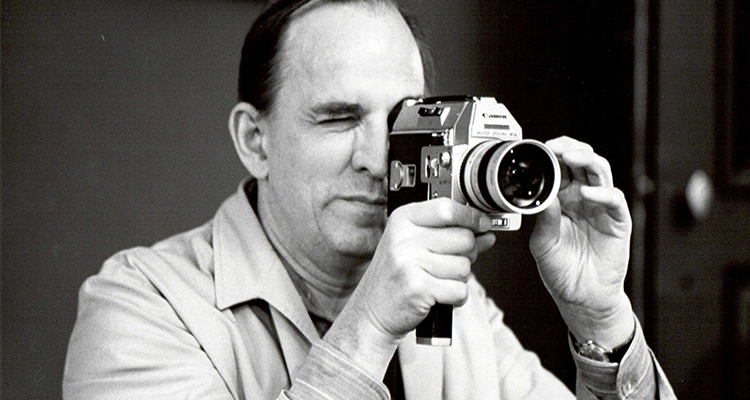

SVEN NYKVIST

“One of the foremost cinematographers in film history, Sven Nykvist was a longtime collaborator of Ingmar Bergman who also worked with other fantastic film directors like Andrei Tarkovsky, Roman Polanski, and Woody Allen. As Liv Ullmann says in this window to the cinematographer, When you talk about Ingmar’s genius and Ingmar’s enormous importance for film, I don’t think you can do that without talking about Sven Nykvist. A poet of light, Ingmar Bergman turned to Sven Nykvist for his openness to filmmaking. His efficient use of available light and experimenting style was alluring and led to a great collaboration between the two filmmakers. Nykvist was a daring filmmaker, which related to the intuitiveness both he and Bergman shared. This daring, however, never opposed the performances of actors for he mixed the importance of aesthetics with the importance of capturing the genuine and human performances of actors. A pioneer of the expressive qualities of light, Sven Nykvist, cinema’s Rembrandt, is a filmmaker to admire and study, and this short documentary With One Eye He Cries is a great way to enter the world of the celebrated cinematographer.” —Edwin Adrian Nieves, A-BitterSweet-Life

“Sufficient time is rarely taken to study light. It is as important as the lines the actors speak, or the direction given to them. It is an integral part of the story and that is why such close coordination is needed between director and cinematographer. Light is a treasure chest: once properly understood, it can bring another dimension to the medium… As I worked with Ingmar, I learned how to express in light the words in the script, and make it reflect the nuances of the drama. Light became a passion which has dominated my life.” —Sven Nykvist

-2.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)