JEAN-PAUL BELMONDO

Jean-Paul Belmondo (born 9 April 1933) is a French film starand one of the actors most closely associated with the New Wave. His laconic, tough guy persona, expressive, unconventional looks, and considerable onscreen charm have made him an icon of French cinema.Jean-Paul Belmondo was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, the son of the sculptor Paul Belmondo. He performed poorly at school but developed a passion for boxing and football. By the time he reached his twenties, Belmondo had decided to pursue a career in acting. After a number of attempts, he was enrolled at the Paris Conservatory to study drama, although his tutors were not optimistic about his prospects.

The coming of the French New Wave in 1959 finally brought Belmondo real stardom. In that year he appeared first in Claude Chabrol’s A Double Tour, which received little notice. It was his next performance, however, as the anti-hero Michel Poiccard inJean-Luc Godard’s A Bout de Souffle, whichmade him an international star. Defiant, reckless, witty and amoral, Belmondo’s Poiccard was the perfect protagonist for Godard’s revolutionary break with the past. The success of the film even resulted in a wave of “Belmondism” in the hipper circles of Paris, with young men modelling themselves on him.

Belmondo revealed unexpected versatility in his next roles, acting opposite Sophia Loren in Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women(1960)and as the enigmatic priest in Jean-Pierre Melville’s World War II drama Leon Morin, Petre (1961). He worked with Godard again for the musical comedy A Woman is a Woman (1961), and with Melville on the film noir/gangster homage Le Doulos (1963).

In Pierrot le Fou (1965), his next collaboration with Godard, Belmondo plays a writer who leaves behind his unhappy life and sets off on a crazy road trip with the babysitter played by Anna Karina. Together they battle gunrunners, gas station attendants, and American tourists in a story that mixes high and pop culture with brilliant artistry. Standing in for Godard, as a man who cannot choose between art and life, Belmondo inhabits his character effortlessly.

Although he had become synonymous at this stage of his career with the films of the New Wave directors, Belmondo also played more mainstream roles in films such as the period swashbuckler Cartouche (1962), the romantic comedy La Chasse a L’Homme(1964) and Philippe De Broca’s action comedy L’Homme de Rio (1964). Capitalising on his increasing drawing power, he founded his own production company called Cerito to produce many of his films.

He continued his association with the Nouvelle Vague directors, starring in Francois Truffaut’s romantic drama Mississippi Mermaid (1969) opposite Catherine Deneuve, Louis Malle’s crime comedy Le Voleur (1967), Claude Chabrol’s black comedyDocteur Popaul (1972), and Alain Resnais ambitious biopic of a famous speculator and con man from the 1930s, Stavisky (1974).

The failure of this last film however, appears to have dissuaded Belmondo from working with the more experimental New Wave filmmakers, and, from this time forward, he began appearing almost exclusively in more commercially oriented features. Among them L’Incorrigible (1975), directed by de Broca, and the crime thrillers Peur Sur la Ville (1975) and L’Alpagueur (1976).

In 1978 Belmondo began a profitable collaboration with director Georges Lautner on the hit comedy thriller Flic ou Voyou. They continued their successful run with Le Guignolo (1979), Le Professionnel (1981), the comedy Joyeuses Paques! (1984), and the mystery L’Inconnu dans la Maison (1992).

A BOUT DE SOUFFLE

Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is a young hoodlum who models himself after Humphrey Bogart. After stealing a car in Marseille, he heads for Paris, gunning down a cop on the way. Once in the capital he meets up with American student Patricia (Jean Seberg), an aspiring journalist who sells copies of the New York Herald Tribune on the Champs-Elysee. Patricia agrees to hide him while he tries to trace a former associate who owes him money so that he can evade the police dragnet and make a break for Italy. But as the authorities close in, she betrays him, leading to a final shoot out in the street.

“To make a film all you need is a girl and a gun.” Jean-Luc Godard’s oft-quoted line might have come from the mouth of any tough-talking, American movie director from Hollywood’s classic era. The fact that it was spoken by a 29-year-old Franco-Swiss intellectual from Paris says much about the cross-cultural pollination that was so crucial to birth of the New Wave and to what is often considered its flagship film: À bout de souffle. Indeed the film’s simple story resembles a classic American film noir, such as those made by Monogram Studios, to whom the film is dedicated. But Godard approached the story in ways that departed radically from past genre archetypes. His years as a critic, his immersion in both high and low culture, his philosophical explorations, all impacted on his debut feature film. As he said in an interview, the film was the result of “a decade’s worth of making movies in my head.” The fact that he was relatively inexperienced and had little knowledge of the practical aspects of filmmaking proved unimportant. What he did have were an accumulation of original ideas, which he applied fearlessly to the aesthetic and technical elements of the film. The results were nothing less than a cinematic revolution.

It was Francois Truffaut who, several years earlier, first sketched out the outline for what would become À bout de souffle. He had been inspired by a true story that had fascinated tabloid France in 1952, when a man named Michel Portail, a petty criminal who had stolen a car, shot a motorcycle policeman who pulled him over, and then hid out for almost two weeks until he was found in a canoe docked in the centre of Paris. One aspect of the story that had appealed to Truffaut was the fact that Portail had an American journalist girlfriend who he had tried to convince to run away with him. Instead she turned him into the police. Truffaut had collaborated with both Claude Chabrol and Godard on the story but had failed to interest any producers. By 1959, Godard, now desperate to catch up with his Cahiers colleagues and make a first feature film, asked if he might revive the project. Truffaut, buoyant with success after the ecstatic reception of Les Quatre cents coups at Cannes, not only agreed, but also helped to convince Georges de Beauregard to produce the film. With a low budget of 510,000 francs (a third of the average cost of a French film at that time), Godard set about casting for the film. He suggested to Beauregard that they hire Jean Seberg, the young actress who had made an uncertain start in pictures on Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan and Bonjour Tristesse, as the American woman. Although most critics had disparaged both films, Godard had written admiringly about Seberg in the pages of Cahiers du cinema. Unimpressed by the director at their first meeting, describing him as “an incredibly introverted, messy-looking young man with glasses, who didn’t look her in the eye when she talked,” she was, nevertheless, encouraged by her husband, a French attorney with directing ambitions of his own, to accept the role. Persuading Columbia Studios to lend her out for the film was less easy, but again her husband stepped in and managed to convince the studio to accept a small cash payment for her participation. As for Jean-Paul Belmondo, Godard had already promised him the lead role in his first film. Belmondo, who was beginning to get lucrative offers from the mainstream film industry, ignored the warning words of his agent who told him, “you’re making the biggest mistake of your life,” and accepted the part. With his cast in place, Godard set about knocking Truffaut’s story outline into a screenplay. His original plan had been to use the outline as it was and merely add dialogue to it. Instead he rewrote the entire story, shifting the emphasis away from Truffaut’s portrayal of an anguished young man who turns to crime out of despair, to that of a young hoodlum with an existential indifference to common morality and the rule of law. Crucially, in the new version, the American woman Patricia comes into the narrative near the beginning and their love story dominates the film.

Filming took place over the summer of 1959. Behind the camera was Raoul Coutard, originally a documentary cameraman for the French army’s information service in Indochina during the war. Coutard’s background suited Godard who wanted the film to be shot, as much as possible, like a documentary, with a handheld camera and the minimum of lighting. This decision was taken for both aesthetic reasons – making the film look like a newsreel – and practical reasons – saving the time setting up lights and tripod. Flexibility was very important to Godard, who wanted the freedom to improvise and shoot whenever and wherever he wanted without too many technical constraints. He and Coutard devised ways – such as using a wheelchair for tracking shots and shooting with specialist lowlight filmstock for nighttime scenes – to make this possible. Godard’s method of directing A bout de souffle was even more radical than his technical innovations. Much to the producer Beauregard’s disapproval, he often only filmed for a couple of hours a day.

Sometimes, when lacking the necessary inspiration, he would cancel the day’s filming altogether. Early on in the shoot, he discarded the screenplay he had written and decided to write the dialogue day by day as the production went along. The actors found this procedure strange and sometimes forgot their lines, however, since the soundtrack was to be post-synchronized later, when the actor’s were lost for words, Godard would call out their lines to them from behind the camera. For Godard the act of making a film was as much a part of its meaning as its content and style. Like “action painting” he felt a film reflected the conditions under which it was made, and that a director’s technique was the method by which a film could be made personal.

Godard’s unorthodox methods continued in the editing suite. His first cut of À bout de souffle was two-and-a-half hours long but Beauregard had required he deliver a ninety-minute film. Rather than cutting out whole scenes, he decided to cut within scenes, even within shots. This use of deliberate jump cuts was unheard of in professional filmmaking where edits were designed to be as seamless as possible. He also cut between shots from intentionally disorienting angles that broke all the traditional rules of continuity. By deliberately appearing amateurish Godard drew attention to the conventions of classic cinema, revealing them for what they were, merely conventions.

It wasn’t only in the montage of images that Godard expressed his personality, but also through the rich depth of references to cinema, literature, and art. À bout de souffle abounds with quotations of movies by directors such as Samuel Fuller, Joseph H. Lewis, Otto Preminger and any number of classic film noirs. There are also quotations and references to writers such as Faulkner, Dylan Thomas, and Louis Aragon, as well as painters like Picasso, Renoir and Klee. Reflecting the film’s cultural heritage, American iconography and influence is everywhere: in the cars (Cadillacs and Oldsmobiles), Michel’s obsession with Humphrey Bogart, and the jaunty, improvised jazz score (played by French pianist Martial Solal). Godard also included his friends in the film. He asked Jean-Pierre Melville to play the celebrated novelist who Patricia interviews at Orly Airport (the other journalists were all played by friends such as André S. Labarthe and Jean Douchet), and Jacques Rivette had a cameo role as a man run over in the street. Godard himself played the informer who recognizes Michel in the street and turns him in. On a deeper level, Godard used the film’s framework to explore some of the themes which preoccupied him, and which he would continue to explore for years to come. Some of the key ideas of existentialism, such as stressing the individual’s importance over society’s rules and the evident absurdity of life, lie at the core of the narrative. Death is an everyday event and generally treated with indifference. The impossibility of love, another central Godardian theme, is played out in the relationship between Michel and Patricia. In the long hotel room scene, which takes up nearly a third of the screen time, the two lovers talk, joke, argue and fool about, but frequently fail to completely understand each other. Michel’s use of slang is often lost on Patricia. That she fails to even understand his dying words sums up the flawed nature of their relationship.

Although Godard was the last of his Cahiers du cinema colleagues to make a film – Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer and Rivette had all completed or at least shot their debuts before À bout de souffle went into production – it was A bout de souffle that became the cornerstone of the New Wave, and is still the film that defines the movement in the public mind. Sight and Sound magazine called it “the group’s intellectual manifesto” and it, more than any other film of the time, captured the New Wave revolt against traditional cinematic form. It also had a youthful exuberance and a pair of leading actors whose style and attitude seemed to epitomize a new generation of youth. In one fell swoop, Godard had succeeded in making the movement representative of the times, defined cinema as the artform of the moment, and personally become one of its most important figures. A bout de souffle was an immediate success. In January 1960, just before the film’s release it won the annual Jean Vigo Prize, given to films made with an independent spirit. The critics were unanimous in their praise, recognizing the film as the greatest accomplishment yet to come out of the New Wave. One wrote: “The terms ‘old cinema’ and ‘new cinema’ now have meaning… with À bout de souffle, the generation gap can suddenly be felt.” Celebrated British critic Penelope Gilliat commented that: “Jean-Luc Godard makes a film as though no one had ever made one before.” When it opened in four commercial cinemas in Paris, it immediately drew large crowds. In the end its profits were estimated to be fifty times the original investment. More importantly, it inspired a generation of filmmakers – for whom Godard had become the embodiment of the New Wave and the archetypal cinematic intellectual – to emulate what he had done. Now, 50 years after its release, the film’s impact and its popularity with critics and the public has not diminished. It continues to influence both directors and the wider culture, and every few years a new generation discovers and falls in love with its unique charm all over again.

Nouvelle Vague (2025)

Nouvelle Vague is a 2025 comedy-drama film directed by Richard Linklater. Starring Guillaume Marbeck as Jean-Luc Godard, Zoey Deutch as Jean Seberg, and Aubry Dullin as Jean-Paul Belmondo, it follows the shooting of Breathless, one of the first feature films of the Nouvelle Vague era of French cinema, in 1959.

Release date: October 31, 2025 (USA)

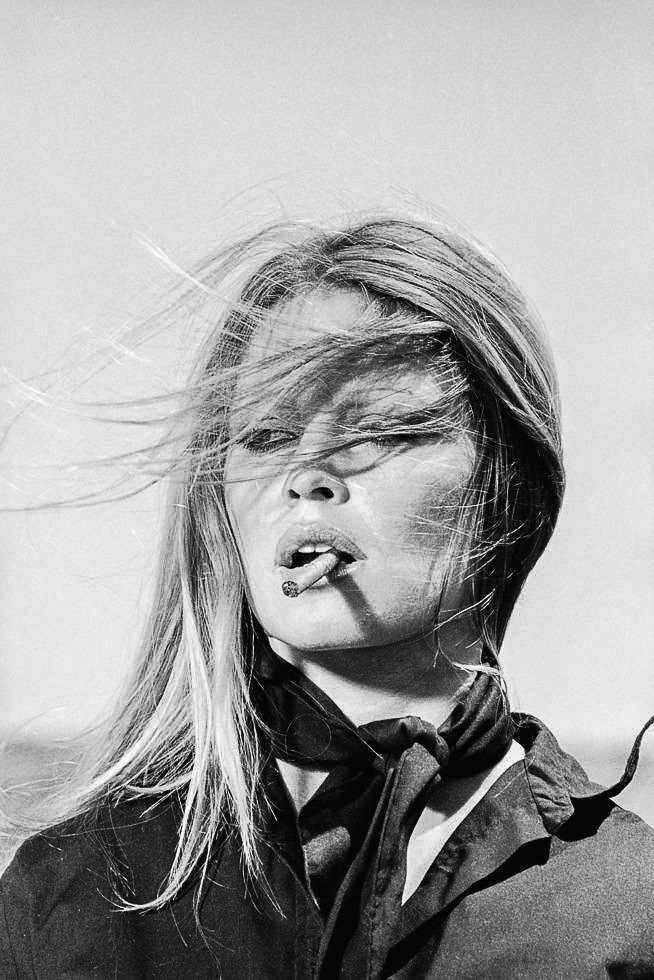

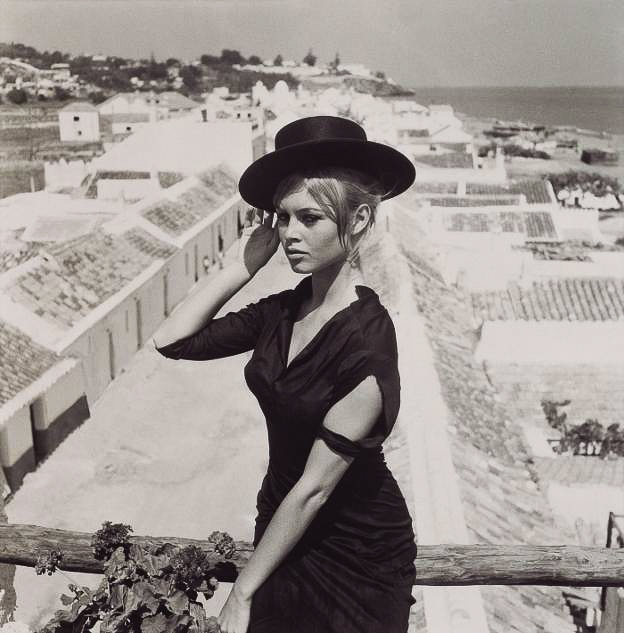

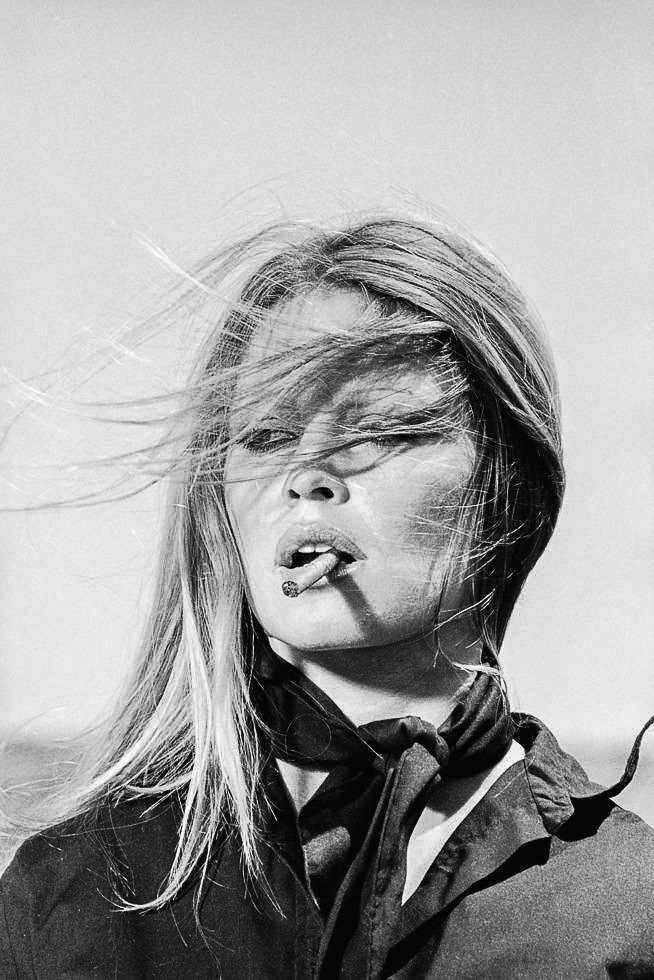

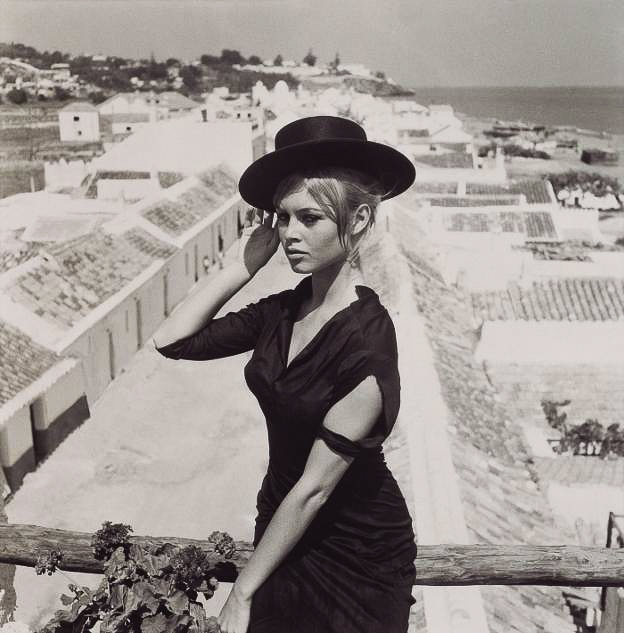

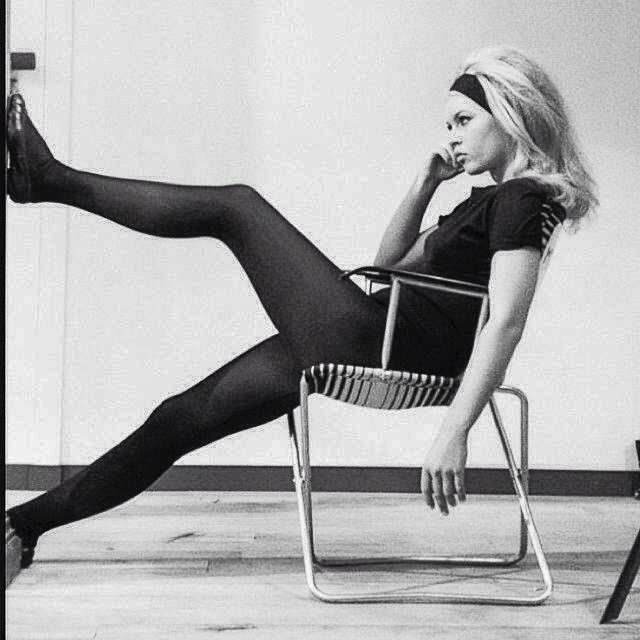

Brigitte Bardot (born September 28, 1934) is a former French model, actress, dancer and singer from a bourgeois background who became an international sex symbol. Discovered by Roger Vadim at age 14, she went on to become France's biggest star and the symbol for a new breed of free 1960s femininity and sexuality. She helped to popularize French cinema, the bikini, free love and St Tropez. Since retiring from acting in the early 1970s she has devoted herself to animal rights and is the founder and chair of The Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the welfare and protection of animals.

Childhood in Paris

Brigitte Bardot was born in her parents’ flat in the 15th arrondissement of Paris on September 28th 1934. Her father, Louis ‘Pilou’ Bardot, was a trained engineer who worked in the family business, Charles Bardot and Company, manufacturers of liquid air and acetylene. Her mother, Anne-Marie ‘Toty’ Mucel was a strict but cultured woman with a particular interest in music and dance. A second child, Brigitte’s younger sister Mijanou, was born in 1938. By then the family had moved to the bourgeois heartland of the 16th arrondissement. In their formative years, both girls were sent to a Catholic school.

At the age of 7, Brigitte’s mother enrolled her to study dance with Marcelle Bourgat, a former star of the Paris Opera. In 1947, at the age of 13, she was accepted as a student at the distinguished Conservatoire National de Danse, where, for three years, she attended the ballet classes of Russian choreographer Boris Knyazev. It was here she developed the perfect posture and elegant way of walking so characteristic of her unique style in the years to come.

Through one of her mother’s contacts, Brigitte was hired to model in a fashion show in 1949. This led to a fashion shoot for the magazine Jardin des Modes, which in turn led to a photo assignment for Elle magazine. She appeared on the cover of the 2 May 1949 issue with the credit, BB. While babysitting for a friend, a budding twenty-one-year-old screenwriter by the name of Roger Vadim picked up this particular edition of Elle and was so taken with the picture that he showed the magazine to film director Marc Allégret, for whom he was working as an assistant at the time. Allégret agreed to give Bardot a screen test for his next film but was unimpressed by the results and didn’t give her the part. It appeared that Brigitte’s acting career was over before it had begun.

Vadim

Roger Vadim, however, was infatuated with Bardot, and remained convinced that she had the makings of a movie star. Some months after the screen test he called her number on a whim and was lucky enough to get Brigitte on the line rather than her over-protective mother, who would almost certainly have hung up on him. Brigitte, however, was excited to hear from him, explaining that her parents were away for the weekend, and she invited him over. Watched over by her grandmother, they spent the afternoon together. A few days later he showed up again, much to the disapproval of Pilou and Toty who were unimpressed by Vadim’s uncut hair and lack of a permanent job. However, the couple continued to see each other, and soon after her fifteenth birthday Brigitte announced that she and Vadim would be married.

Brigitte’s parents did everything they could to keep her from making what they believed to be such a serious mistake. They wanted her to get her high school baccalaureate. They wanted her to continue with her dancing. They insisted that she could not marry until she was eighteen. Pilou even threatened Vadim with a revolver, warning him that if he ever touched his little girl, he’d use it. The harder Brigitte tried to persuade them, the more they resisted. It was all too much for the Brigitte, who, one evening when the rest of the family was out, put her head in the oven and turned on the gas. By chance her parents returned early and managed to save her in time.

Bowing to the inevitable, Brigitte’s parents allowed their daughter to continue seeing Vadim, who was already preparing her for future stardom by insisting she take acting classes. Meanwhile she continued modelling and undertook her first and only contract as a professional dancer on a 15-day cruise ship around the Atlantic Islands.

Back in Paris, Brigitte’s film career began with a small part in Jean Boyer’s 1952 film Le Trou normand. It was an inauspicious start for Bardot who didn’t like the role she played, didn’t feel she knew what she was doing, and was not happy with her acting or the slow and mechanical process of making films. Nevertheless, almost immediately after, she went in front of the camera again when Vadim secured her the title role in Willy Rozier’s Manina – La fille sans voile (The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter). Shot in the summer of 1952, Brigitte spent most of the film scantily clad in a bikini. Her father was outraged and demanded cuts. Rozier compromised by agreeing to allow a judicial referee to see the film before it was officially released. In November 1952, with Brigitte now eighteen, the referee ruled that the film was decent and could be shown without any risk to her honour.

In December Brigitte and Vadim were finally married. There were two ceremonies. The first was a civil ceremony at the town hall that served the 16th arrondissement. The second took place the following day at Notre Dame de Grace in Passy. After a brief honeymoon at Megeve, the couple returned to their own one-bedroom flat on the rue Chardon-Lagache, a gift from Brigitte’s parents.

During their first few years together, Bardot and Vadim developed a remarkable partnership. He shaped and influenced the way she spoke, what she wore, and her famous pout. Most importantly he changed the colour of her hair, turning her into a blonde. “Whenever I walked or undressed or ate breakfast,” she later remembered, “I always had the impression he was looking at me with someone else’s eyes and with everyone’s eyes. Yet, I knew he wasn’t seeing me, but through me his dream.”

Having created this new Bardot, Vadim signed her up with an influential agent. Together they got her cast in a quick succession of mostly forgettable movies, including La Portrait de son père (His Father’s Portrait, 1953), Act of Love(1953) starring Kirk Douglas, Si Versailles m’etait conte (Affairs in Versailles, 1954). Tradita (Concert of Intrigue, 1954), and Futures Vedettes (Sweet Sixteen, 1955). This last film was co-written by Vadim and directed by Marc Allégret, who had now reconsidered his earlier assessment of the young actress. Vadim and Brigitte collaborated on the dialogue together, modifying the lines to fit her carefully crafted persona.

Making Waves

But none of these film appearances had anything like the impact of Brigitte’s appearance at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival. The beach at Cannes was already crowded with stars when Bardot showed up in a bathing suit. Immediately, the photographers, orchestrated by Vadim, focused their attention on her. They photographed her on the beach and in front of the Carlton hotel. Then a photo opportunity was arranged for a group of famous stars on the aircraft carrier Midway anchored offshore. Brigitte managed to get herself invited too and when she slipped off her raincoat to reveal herself wrapped in a tiny dress, the sailors went wild. Still a relative unknown, she had stolen the limelight from some of the biggest film stars in the world.

Her growing fame brought the offer of a role in a British comedy, Doctor at Sea, staring Dirk Bogarde. At a press conference for the film, Brigitte packed the ballroom at the Dorchester Hotel in London and captivated the journalists with her witty replies to their hackneyed questions. “She is every man’s idea of the girl he’d like to meet in Paris,” wrote the film-critic Ivon Addams.

Back in France she worked with Michele Morgan and Gérard Philipe in Les Grandes Manoeuvres (Summer Maneuvers, 1955), as the sexy temptress in La Lumière d’en Face (The Light Across the Street, 1955), as Andraste in Robert Wise’sHelen of Troy (1956), bathing in milk in Mio Figlio Nerone (Nero’s Big Weekend, 1956) and tantalizing in the screwball comedy En Effeuillant la Marguerite (Mam’zelle Striptease, 1956). All the time, Vadim continued to feed stories about her to an increasingly hungry press.

And God Created Woman

Roger Vadim was still only 26 years old when he wrote the screenplay for the film that would catapult Bardot to international stardom and launch his own directing career. He had been planning the move for years but the breakthrough came when he met and teamed up with another ambitious young man, producer Raoul Lévy. Vadim’s screenplay was a melodramatic tale of love, marriage and betrayal set in Saint-Tropez. Levy not only agreed to back the project, he was willing to let Vadim direct, a very unusual concession at the time when most first-time directors were in the forties or fifties. Vadim also managed to persuade him that that film should be in colour and wide-screen Cinemascope. Levy then set to work trying to find financial partners but it wasn’t easy as Vadim later recalled, “In 1955 Raoul was a hard-up producer and I was a novice writer. Our first project brought shrugs of disbelief from film people who advised us to buy a lottery ticket instead.” Eventually a former band leader, Ray Ventura, agreed to co-produce the film, and once they had signed up the established actor Curt Jurgens and Columbia studios had agreed to distribute it, they had enough money to begin production.

The film was shot quickly in May and June 1956, on location in St Tropez and at the Victorine Studios in Nice. In the story Bardot plays eighteen-year old orphan Juliette, a seductive beauty whose habit of sunbathing naked and walking around the town barefoot, attracts the attention of various men. Her suitors include wealthy middle-aged businessman Eric Carradine (Curt Jurgens) and the local Tardieu brothers, Antoine (Christian Marquand) and Michel (Jean-Louis Trintignant). Sparking rivalry between the brothers by agreeing to marry Michel but sleeping with Antoine, she also continues to toy with Carradine’s affections, putting on a frenzied dance for him in the neighbourhood bar, leading to a confrontation and a final shoot out.

While the storyline was relatively conventional, it was the audacity of Bardot’s performance and the frank portrayal of sexuality on screen that made contemporary audiences react so strongly. “She does whatever she wants,” Eric says of Juliette, “whenever she wants.” This was a new kind of woman, untamed and untroubled by conventional morality; Vadim had captured perfectly what was unique and special about Brigitte’s character and people responded. They didn’t know whether to be shocked or excited. The censor reacted predictably with outrage and demanded cuts. He reprimanded Vadim for the scene in which Bardot gets out of bed and walks naked across a room and insisted it be cut. Vadim told him he had imagined the scene, that in fact she was wearing a long shirt in the shot. The censor remained sure he’d seen her naked, forcing Vadim to rerun the film again to prove otherwise. “That was one of the most amazing things about Brigitte’s presence on film,” Vadim later recalled, “people often thought she was naked when she wasn’t.”

When Et Dieu… Créa la femme (And God Created Woman) opened in Paris in 1956 the reviews were damning. “What a terrible image this film will give of France as portrayed by the vulgarity of Mlle Bardot,” wrote one. Initially the box office returns were poor and it looked like the film would sink without trace; that is until it began opening around the rest of the world. Before the film opened in London the British censor demanded cuts, but it didn’t stop the film being released in cinemas across the country to great success. In America the Catholic Church tried to have the film banned but the scandal only added to the publicity. It became the first French film ever to out-sell a homegrown blockbuster when it topped the charts ahead of big Hollywood films like The Ten Commandments. Life magazine commented, ‘Since the Statue of Liberty, no French girl has ever shone quite as much light on the United States.’ Based on the unbelievable response to the film throughout the rest of the world, it was re-released and became a huge success in France too.

New Life, New Loves

While filming Et Dieu… Créa la femme, Brigitte had fallen in love with her co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant. At first it seemed merely an attempt to make Vadim jealous, but when he didn’t get jealous it became something more serious. As for Vadim, he had seen the end coming for some time: “I’d liberated Brigitte and shown her how to be truly herself. That was the beginning of the end of our marriage. From that moment, our marriage went downhill.” For Bardot, Trintignant offered an alternative to a life of constant hectic socializing in film studios and cocktail parties. He was a quiet young man who read poetry, and, unlike her stormy relationship with her husband, they never argued. Her separation from Vadim, which took place in 1957, was a civilized affair. “I’ve never seen any divorce go as smoothly,” he later recalled. They stayed good friends and he remained an important confidant for her in the years to come.

In the wake of Et Dieu créa la femme, Bardot was a hot property and continued making films at a steady pace, includingLa Mariée est trop belle (The Bride Is Much Too Beautiful, 1956) with Louis Jordan, La Parisienne (1957), and Les Bijoutiers du clair de lune (Heaven Fell That Night, 1958) again directed by Jean Vadim. Otto Preminger wanted to cast her as the wayward daughter in his adaptation of Francoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, but on Vadim’s advice she turned it down. She also turned down an opportunity to make a film with Frank Sinatra because it would mean upping sticks and moving to America. Instead she starred with Jean Gabin in En cas de malheur (Love Is My Profession, 1958).

At the end of 1958 Cinémonde magazine voted Bardot and Gabin their number one stars. But she wasn’t just popular in France; she was beginning to top popularity lists in countries across the world. Such immense fame brought with it the constant attention of the press, who pursued her relentlessly. She often felt trapped and admitted to friends that she felt she was missing out on a normal life. Her relationship with Jean-Louis Trintignant had lasted only six months, after which she had even briefer flings with actor Gustavo Rojo and singer Gilbert Becaud.

Looking for a refuge, she bought a house in the small coastal town of St Tropez and began spending whatever time off she had there. It was here she met the singer Sacha Distel. Their whirlwind love affair became front-page news. Photographers followed them from St Tropez to Paris. Mob scenes greeted them in Italy when they attended the Venice Film Festival together in 1958. For a while there was serious talk of marriage but the burden of being engaged to Brigitte became too difficult for Distel to bear. “She needed the man she was in love with to be with her constantly, to do the things she wanted to do, and to take second place,” he later lamented, although his association with her did no harm to his budding career. By the end of the summer their romance was just a memory.

Charrier

Brigitte’s next film was a comedy set in World War II, Babette s’en Va-t-en Guerre (Babette Goes to War, 1959). Her co-star was a good-looking young twenty-two-year-old actor named Jacques Charrier. During shooting in Paris and London, Brigitte quickly fell for Charrier. After filming they went on holiday together to Chamonix-les-Houches. Staying in a chalet, isolated by a snowstorm, Brigitte got pregnant. As soon as she found out she called Vadim and asked his advice. He knew that she didn’t like children, yet he advised her to have the child because if she didn’t she might regret it. When he found out, Charrier insisted that not only must she have the child but they must get married as soon as possible.

The ceremony took place in a quiet Paris suburb. Despite attempts to keep it secret, someone tipped off the press who besieged the church. During the ceremony there were flashbulbs going off constantly and an argument broke out between Brigitte’s father and the local mayor who was conducting the event. It was an ill omen for a marriage that seemed jinxed from the start. First Charrier suffered an attack of appendicitis and was forced into hospital. Before he had recovered, Brigitte had to start work on her next film, Voulez vous dancer avec moi (Come and Dance With Me). No sooner was Charrier out of hospital than he was called up by the army for military service. In the barracks, he was taunted mercilessly by the other men. He lost 20 pounds, had a breakdown and tried to slit his wrists.

Released for a year on compassionate grounds, he returned to live with Brigitte in her Paris apartment. Already the press were camped outside awaiting the birth of the child. It became virtually impossible for her to leave the apartment. ‘It was inhuman what the press put me through,” Bardot recalled in an interview many years later. “I couldn’t take a walk. I couldn’t go out. I couldn’t go to see my doctor. I couldn’t even go to have my baby in a hospital. I was encircled by the press from all over the world.” Finally on Monday 11 January 1960, Nicholas Charrier was born. However his birth failed to bring out the maternal instincts Vadim had predicted. “How could you expect me to raise a child when I still needed my mother?” She commented later. Bardot would only see Nicholas intermittently through his childhood, and not until she was in her sixties and he was married with two children, would they have a lasting reconciliation.

Cracking Up

Six weeks after the birth, Brigitte had a small part in L’Affair d’une nuit (It Happened at Night, 1960). This was followed by the leading role in Henri-Georges Cluzot’s La Verite (The Truth, 1960). In the film she played Dominique, a young girl from the provinces who comes to Paris and gets caught up in the bohemian life. When she discovers her lover is having an affair, she kills him and is put on trial for murder. Unable to explain to anybody her inner torment, she slashes her wrists.

Filming proved fraught with Brigitte struggling to cope with the pressures of constant press intrusion and the jealousy of her husband over her love scenes with handsome young co-star Sami Frey. To calm her down Cluzot prepared her for certain scenes by doping her with tranquillizers and whiskey. The film was a critical and commercial success and Brigitte later considered it her favourite film, but Cluzot’s often-tyrannical methods did nothing to help her nerves. There were fights between them on the set. During one of these, Brigitte slapped the director and called him a psychopath. The press speculated that the two of them were having an affair, though the truth was she was actually seeing her co-star Frey.

By the end of the filming Brigitte was at the end of her tether. In love with Sami Frey but unsure whether she wanted to end her marriage to Charrier, she left them both to take a holiday with her friend Mercedes Zavka in a secluded villa in a tiny coastal village where the press would never think to find her. For the first couple of weeks, the pair lived like carefree recluses. Brigitte went under a false name and wore a headscarf and sunglasses when outside. Inevitably a photographer spotted her. The word got out and soon the paparazzi were camped outside the villa.

The next day was Brigitte’s 26th birthday. She tried to carry on as normal, having lunch at a beachside restaurant, but somebody took a photograph. It was the last straw for Brigitte. That evening she went for a walk and didn’t come back. She was found sitting at the bottom of the garden. She’d slashed her wrists and taken an overdose of barbiturates. An ambulance was called and took her to a clinic in Nice. The next day doctors at the clinic issued a statement saying that she was out of danger, although adding that she was suffering from acute depression. They also acknowledged she’d come within minutes of dying. Brigitte left the clinic on the 2nd of October and returned to her house in St Tropez. Within a few weeks she was seen shopping in the village as normal accompanied by Roger Vadim who had helped her through the crisis. Bardot’s divorce from Jacques Charrier was finalized in 1962. In an uncontested plea, Charrier was awarded custody of Nicholas.

The Last Act

Following Viva Maria!, Bardot’s film appearances became more infrequent. She had a cameo in Godard’s Masculin, Feminin (1966), starred in the woeful A Coeur joie (Two Weeks in September, 1967), appeared opposite Alain Delon in the Edgar Allan Poe compendium Histoires extraordinaires (1968), and opposite Sean Connery in the lacklustre westernShalako (1968). The attractions of the movie business had long faded for her. “The cinema is an absurd world. I decided to live my life as I am, not as anyone else wanted me to be. When I’m working, that’s fine. But when I stop and think about all of that, I am horrified by the extraordinary image that has been created around me."

Her indifference lead to some cavalier choices throughout her career, especially towards the end. Her final films includedLes Femmes (1969), L’Ours et la poupée (The Bear and the Doll, 1970), Boulevard du Rhum (Rum Runners, 1971), andLes Petroleuses (The Legend of Frenchie King, 1971). Fittingly, her final film before she announced her retirement was directed by Roger Vadim. Don Juan ou si Don Juan était une femme (1973) starred Bardot as a female Don Juan. It should have been a memorable swansong but instead turned out to be another disappointment. In 1973, at the age of 39, Brigitte had had enough.

FRENCH NEW WAVE CINEMA DIRECTORS >>>

FRENCH NEW WAVE CINEMA-MAJOR WORK >>>

French actress Brigitte Bardot has died aged 91, her foundation says.

-2-2-3.jpg)

.jpg)