"McNamara might be sneaky and self-serving, but his sheer vigour and unapologetic brainpower are as refreshing as iced water."

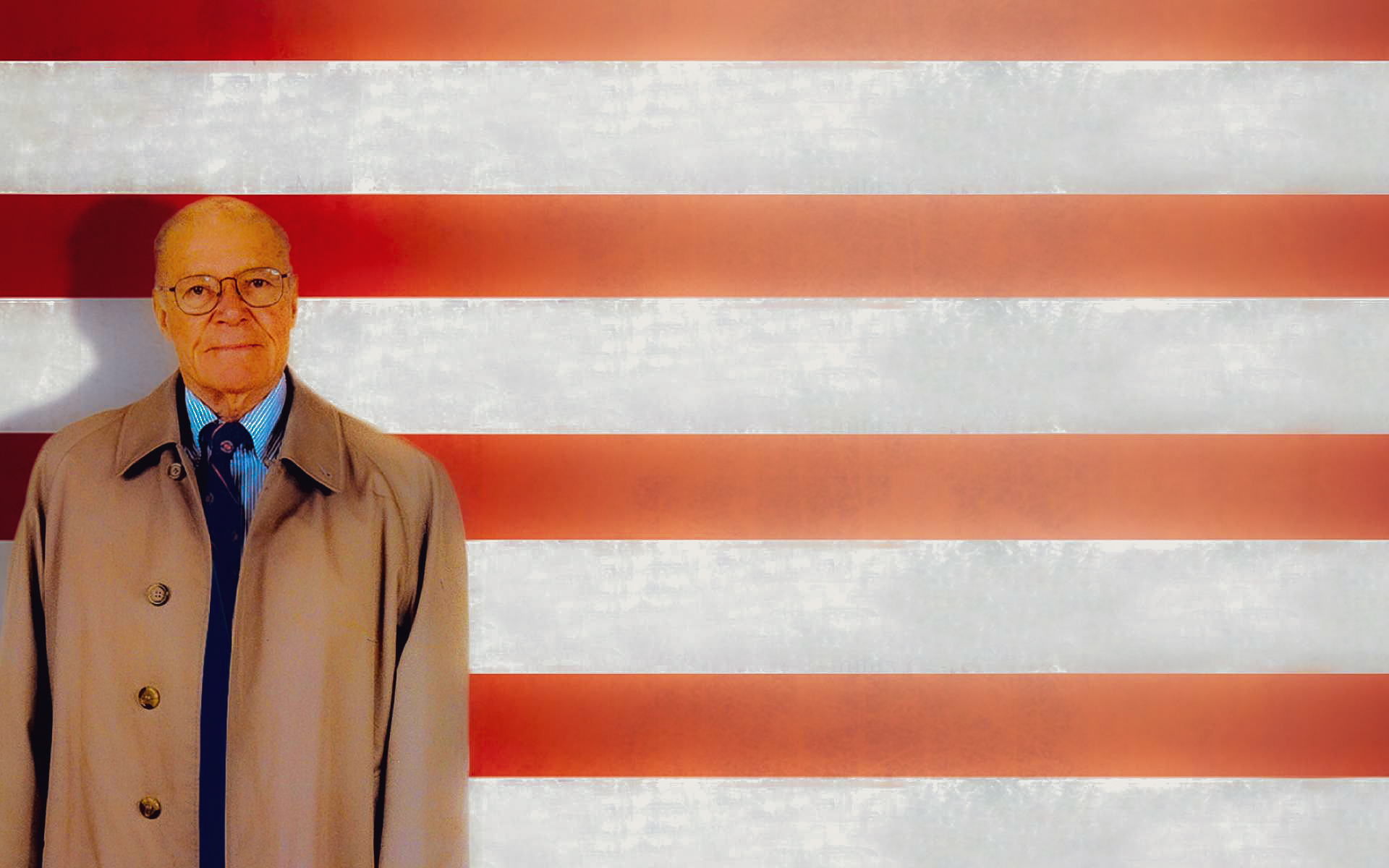

Robert McNamara agreed to talk with Morris for an hour or so, supposedly for a TV special. He eventually spent 20 hours peering into Morris' "Interrotron," a video device that allows Morris and his subjects to look into each other's eyes while also looking directly into the camera lens.

McNamara was 85 when the interviews were conducted -- a fit and alert 85, still skiing the slopes at Aspen. Guided sometimes by Morris, sometimes taking the lead, he talks introspectively about his life, his thoughts about Vietnam, and, taking Morris where he would never have thought to go, of his role in planning the firebombing of Japan, including a raid on Tokyo that claimed 100,000 lives. He speaks concisely and forcibly, rarely searching for a word, and he is not reciting boilerplate and old sound bites; there is the uncanny sensation that he is thinking as he speaks.

His thoughts are organized as "11 Lessons From the Life of Robert McNamara," as extrapolated by Morris, and one wonders how the current planners of the war in Iraq would respond to lessons No. 1 and 2 ("Empathize with your enemy" and "Rationality will not save us"), or for that matter No. 6 ("Get the data"), No. 7 ("Belief and seeing are both often wrong") and No. 8 ("Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning"). I cannot imagine the circumstances under which Donald Rumsfeld, the current Secretary of Defense, would not want to see this film about his predecessor, having recycled and even improved upon McNamara's mistakes.

McNamara recalls the days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the world came to the brink of nuclear war (he holds up two fingers, almost touching, to show how close -- "this close"). He recalls a meeting, years later, with Fidel Castro, who told him he was prepared to accept the destruction of Cuba if that's what the war would mean. He recalls two telegrams to Kennedy from Khrushchev, one more conciliatory, one perhaps dictated by Kremlin hard-liners, and says that JFK decided to answer the first and ignore the second. (Not quite true, as Fred Kaplan documents in an article at Slate.com.) The movie makes it clear that no one was thinking very clearly, and that the world avoided war as much by luck as by wisdom.

And then he remembers the years of the Vietnam War, inherited from JFK and greatly expanded by Lyndon Johnson. He began to realize the war could never be won, he says, and wrote a memo to the president to that effect. The result was that he resigned as defense secretary. (He had dinner with Katharine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, and told her "Kay, I don't know if I resigned or was fired." "Oh, Bob," she told him, "of course you were fired.") He didn't resign as a matter of principle, as a British cabinet minister might; it is worth remembering that a few months later Johnson, saying he would not stand for reelection, also effectively resigned.

McNamara is both forthright and elusive. He talks about a Quaker who burned himself to death below the windows of his office in the Pentagon and finds his sacrifice somehow in the same spirit as his own thinking -- but it is true he could have done more to try to end the war, and did not, and will not say why he did not, although now he clearly wishes he had.

With disarming candour and good humour, McNamara takes us through his brilliant career as the IBM technocrat who brought new-fangled punch-card efficiency techniques to bear as a military aide to General Curtis LeMay in the second world war, helping to increase the number of buildings annihilated and civilians incinerated in the firebombing campaign of Japanese cities that preceded Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

McNamara says quite openly that he and LeMay could have been tried as war criminals if the result had gone the other way. To my shame, I admit I had no idea about the enormity of these pre-nuclear campaigns; I suspect many more are in the dark and, for this reason alone, Morris's movie deserves to be shown on every school and university campus.

.jpg)

.jpg)