Prepared for the New York State Writers Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies at Pennsylvania State University:

It is an eerie film, perhaps a masterpiece if the documentarist's art, certainly a sinister endorsement of a doctrine of mass murder. But is it a war crime?

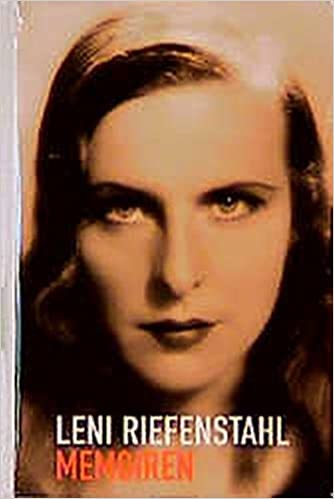

Leni Riefenstahl was the golden girl of the German film industry. She had starred in a series of mystical, location-shot adventure films in the 1920's and early 1930's, directed and written by Arnold Fanck, a uniquely German genre called the "mountain film." On screen, Riefenstahl was beautiful, strong, and self-confident, and she projected these qualities off-screen, as well. In an age before women commonly directed large commercial film projects, Riefenstahl's assignment to direct The Blue Light in 1932 made her more than a curiosity; her cinematic style was, in the term film theorists of the day like Rudolph Arnheim used, "plastic": she saw the medium as a unique form of expression, not merely a manner for transferring ideas and plots from the theatre or literature. Her camera moved, and she understood, at a deep level, the mysterious power of the cinematic spectacle of movement, sound, and mise-en-scene to captivate audiences. Her work on the mountain films had been part of a pinnacle for the German film industry, when the expressionist masterworks of Fritz Lang (Metropolis) and F. W. Murnau (The Last Laugh) had made the German industry the envy of the world critical establishment for its command of these qualities, demonstrated in a hundred or more films made between 1919 and 1932.

But when the German film industry emptied itself of its great talents in the wake of the advent of Adolph Hitler in 1933, Riefenstahl refused to join the river of cinematic refugees to France, England, and the U.S.. She would forever after claim to be "apolitical," but her first meeting with Adolph Hitler, in 1932, was propitious. Hitler was an admirer of The Blue Light, and presciently recognized the power of the cinema as a mass persuasion instrument. Riefenstahl made a short film about the 1933 Nazi party rallies in Nuremberg; though she had only a few days to prepare before the event, the film, released as "Victory of Faith," was an ambitious and aesthetically advanced film. Now, with considerably more time to plan, Riefenstahl took over the planning of a film about the 1934 rally originally begun by documentarian Walter Ruttmann. What Ruttmann had planned as an explicitly rhetorical film, Riefenstahl saw as a cinematic paean to the race mythologies of Nazism, expressed through the geometry of its mass rituals and the solitary figure of its strange, strutting god, Adolph Hitler. Although it was long alleged that Riefenstahl had a hand in planning the massive rallies themselves, helping to design their staging so that the event would be more photogenic, Hitler's minister of the interior and court architect Albert Speer denied this many years later; the striking Art Deco blockiness of the outdoor rallies, with their searchlights turned upward like pillars of fire, was his own, and the only major concession to Riefenstahl's crew was the provision of a huge elevator that allowed for her spectacular crane shots.

But when the German film industry emptied itself of its great talents in the wake of the advent of Adolph Hitler in 1933, Riefenstahl refused to join the river of cinematic refugees to France, England, and the U.S.. She would forever after claim to be "apolitical," but her first meeting with Adolph Hitler, in 1932, was propitious. Hitler was an admirer of The Blue Light, and presciently recognized the power of the cinema as a mass persuasion instrument. Riefenstahl made a short film about the 1933 Nazi party rallies in Nuremberg; though she had only a few days to prepare before the event, the film, released as "Victory of Faith," was an ambitious and aesthetically advanced film. Now, with considerably more time to plan, Riefenstahl took over the planning of a film about the 1934 rally originally begun by documentarian Walter Ruttmann. What Ruttmann had planned as an explicitly rhetorical film, Riefenstahl saw as a cinematic paean to the race mythologies of Nazism, expressed through the geometry of its mass rituals and the solitary figure of its strange, strutting god, Adolph Hitler. Although it was long alleged that Riefenstahl had a hand in planning the massive rallies themselves, helping to design their staging so that the event would be more photogenic, Hitler's minister of the interior and court architect Albert Speer denied this many years later; the striking Art Deco blockiness of the outdoor rallies, with their searchlights turned upward like pillars of fire, was his own, and the only major concession to Riefenstahl's crew was the provision of a huge elevator that allowed for her spectacular crane shots.

Speer's protests don't dim the film's remarkable use of the medium, or the clear internal evidence that the rallies were designed as much to be looked at as to be marched in. Riefenstahl's film privileges the film viewer with an impossible, perfect view of the proceedings; in a weird, disconcerting way, we ordinary film viewers become, for the running time of the film, the protagonist of Nazism, in the same way that Hitler skillfully gave ordinary Germans a feeling of command over history and politics. Indeed, while film analysts often (justifiably) note the orchestrated editing and vast, abstract human landscapes of the outdoor sequences, Riefenstahl invests considerable weight in Hitler himself. The scenes of his climactic speech to the multitudes in the indoor party hall, interminable as discourse, become mesmerizing as political theater, as Hitler calculates every gesture, expression, and intonation as a facet of a screen character, "Hitler, leader of his people." One moment he is expansive, laughing and joking with his people, the next, he is abstracted, so lost in the deep responsibilities of leadership that he seems not to be able to hear the ecstatic applause as he looks over his notes. Hitler's moves, every one of them, whether bellicose or bathetic, are designed to elicit a Pavlovian response from the crowd, and, with the help of Riefenstahl's editing, they do. It is intriguing to wonder if some of the postwar era's genocidal dictators, Hussein, Amin, and others, borrowed some of their moves from Hitler. This is the cult of personality raised to a kind of rapture: from the first minutes of the opening stanza of the film, when Hitler descends from the clouds, transubstantiated from some Teutonic heaven to the earthly precincts of Nuremberg, he is both in the world and out of it, the seething godhead of a demonic political religion. That the world did not take him seriously, or judge him against a less relative standard of morality - in the year after Triumph of the Will's release, Hitler as named Time magazine's "man of the Year" - is no fault of Leni Riefenstahl's, for the Hitler she gives us is plainly a weapon of mass destruction.

When director Frank Capra was commissioned by the U.S. government to make what became the Why We Fight series of propaganda films in World War II, he screened a copy of Triumph of the Will which had been seized by the U.S. Customs office. When he subjected the film to close analysis, what he saw startled him: the ability of his own films to recruit and direct mass emotions for fictional purposes could be just as easily turned to political, even violent purposes. Susan Sontag called her far-reaching essay in the film "Fascinating Fascism," and the term is incisive. In part to Triumph of the Will, we owe terrifying confirmation of our now axiomatic belief in the dangerous power of the media. It is a spectacle from which we seek to turn away, but from which we cannot - and should not.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)