_

And, indeed, I will ask on my own account here, an idle question: which is better—cheap happiness or exalted sufferings? Well, which is better?---Fyodor Dostoevsky ---Notes from Underground Fyodor Dostoevsky ---Notes from Underground Even now, so many years later, all this is somehow a very evil memory. I have many evil memories now, but ... hadn’t I better end my “Notes” here? I believe I made a mistake in beginning to write them, anyway I have felt ashamed all the time I’ve been writing this story; so it’s hardly literature so much as a corrective punishment. Why, to tell long stories, showing how I have spoiled my life through morally rotting in my corner, through lack of fitting environment, through divorce from real life, and rankling spite in my underground world, would certainly not be interesting; a novel needs a hero, and all the traits for an anti-hero are expressly gathered together here, and what matters most, it all produces an unpleasant impression, for we are...

Hope

To be human is to be a miracle of evolution conscious of its own miraculousness — a consciousness beautiful and bittersweet, for we have paid for it with a parallel awareness not only of our fundamental improbability but of our staggering fragility, of how physiologically precarious our survival is and how psychologically vulnerable our sanity. To make that awareness bearable, we have evolved a singular faculty that might just be the crowning miracle of our consciousness: hope.--

Erich Fromm

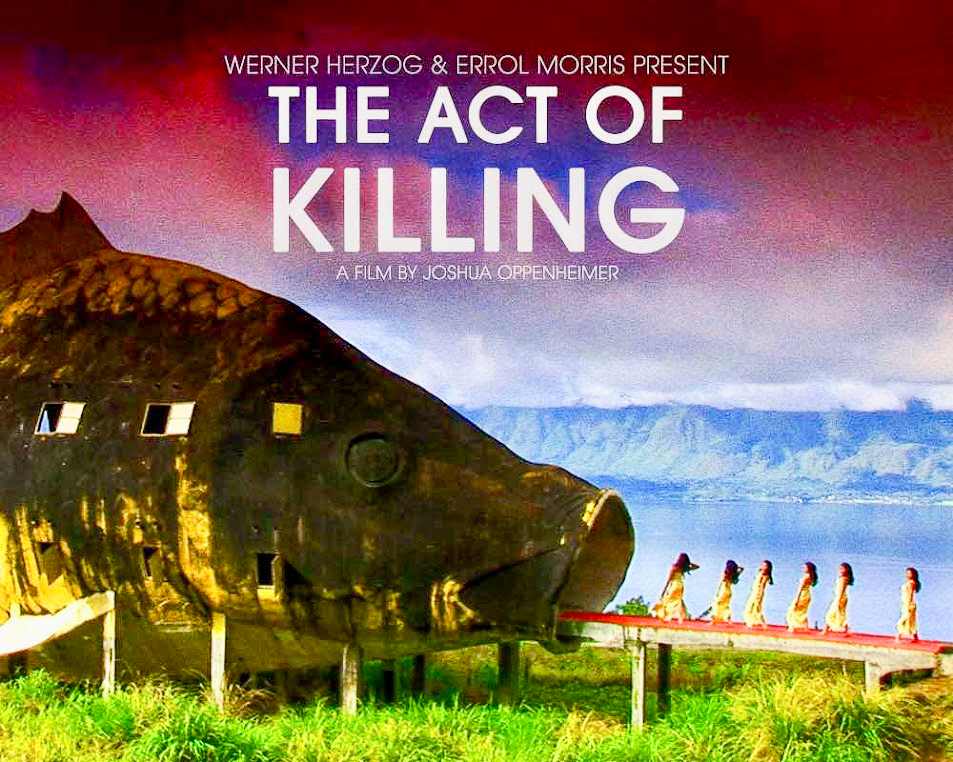

Aguirre, the Wrath of God (Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes , 1972)

Werner Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” (1973) is one of the great haunting visions of the cinema.

"On this river God never finished his creation".

The captured Indian speaks solemnly to the last remnants of a Spanish expedition seeking the fabled El Dorado, the city of gold. A padre hands him a Bible, “the word of God.” He holds it to his ear but can hear nothing. Around his neck hangs a golden bauble. The Spanish rip it from him and hold it before their eyes, mesmerized by the hope that now, finally, at last, El Dorado must be at hand. “Where is the city?” they cry at the Indian, using their slave as an interpreter. He waves his hand vaguely at the river. It is further. Always further.

Film tells the story of the doomed expedition of the conquistador Gonzalo Pizarro, who in 1560 and 1561 led a body of men into the Peruvian rain forest, lured by stories of the lost city. The opening shot is a striking image: A long line of men snakes its way down a steep path to a valley far below, while clouds of mist obscure the peaks. These men wear steel helmets and breastplates, and carry their women in enclosed sedan-chairs. They are dressed for a court pageant, not for the jungle.

The music sets the tone. It is haunting, ecclesiastical, human and yet something else. It is by Florian Fricke, whose band Popol Vuh (named for the Mayan creation myth) has contributed the soundtracks to many Herzog films.

The music sets the tone. It is haunting, ecclesiastical, human and yet something else. It is by Florian Fricke, whose band Popol Vuh (named for the Mayan creation myth) has contributed the soundtracks to many Herzog films.

If the music is crucial to “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” so is the face of Klaus Kinski. He has haunted blue eyes and wide, thick lips that would look sensual if they were not pulled back in the rictus of madness. Here he plays the strongest-willed of the conquistadors. Herzog told me that he was a youth in Germany when he saw Kinski for the first time: “At that moment I knew it was my destiny to make films, and his to act in them.”

"Never has Klaus Kinski been more unhinged than as the leader of this crew"

Aguirre rules with a reign of terror. He stalks about the raft with a curious lopsided gait, as if one of his knees will not bend. There is madness in his eyes. When he overhears one of the men whispering of plans to escape, he cuts off his head so swiftly that the dead head finishes the sentence it was speaking. Death occurs mostly offscreen in the film, or swiftly and silently, as arrows fly softly out of the jungle and into the necks and backs of the men. The film’s final images, among the most memorable I have ever seen, are of Aguirre alone on his raft, surrounded by corpses and by hundreds of chattering little monkeys, still planning his new empire.

The filming of “Aguirre” is a legend in film circles. Herzog, a German director who speaks of the “voodoo of location,” took his actors and crew into a remote jungle district where fever was frequent and starvation seemed like a possibility. It is said Herzog held a gun on Kinski to force him to continue acting, although Kinski, in his autobiography, denies this, adding darkly that he had the only gun. The actors, crew members and cameras were all actually on rafts like those we see, and often, Herzog told me, “I did not know the dialogue 10 minutes before we shot a scene.”Herzog's 1999 documentary My Best Fiend, about his leading man Klaus Kinski, tells the incredible story of the insanely dangerous shooting conditions and near-murderous rows between director and star.

The film is not driven by dialogue, anyway, or even by the characters, except for Aguirre, whose personality is created as much by Kinski’s face and body as by words. What Herzog sees in the story, I think, is what he finds in many of his films: Men haunted by a vision of great achievement, who commit the sin of pride by daring to reach for it, and are crushed by an implacable universe. One thinks of his documentary about the ski-jumper Steiner, who wanted to fly forever, and became so good that he was in danger of overshooting the landing area and crushing himself against stones and trees.

FILM DIRECTORS - WERNER HERZOG >>>

%20DVD%20cover%20111.jpg)

.jpg)