_

Hope

Links

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

FILM DIRECTORS--Pedro Almodóvar

Many famous directors retreat to the privacy of their own screening rooms, but Pedro Almodóvar still likes to see movies in theatre. He lives off a park on the western side of Madrid, and the art houses are clumped together near Plaza de España, not far away. He tries to go at least once a week. If a studio sends him a screener on DVD and he likes the movie, he will watch it a second time in a cinema.

At the age of seventeen, he came home from Catholic school and told his parents that he was moving to Madrid. His father, he recalls, “threatened to turn me in to the National Guard.” Pedro replied, “Turn me in. I’m leaving.”

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988)

Pepi, Luci, Bom was Almodóvar’s first feature as a director, but it was 1988’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown that launched him into the cinematic pantheon. The dark dramedy starred Carmen Maura and was an early breakout role for Antonio Banderas, who has remained a collaborator with Almodóvar to this day. The film, about a woman who is abandoned by her married boyfriend, was nominated for the 1988 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and won five Goya Awards.

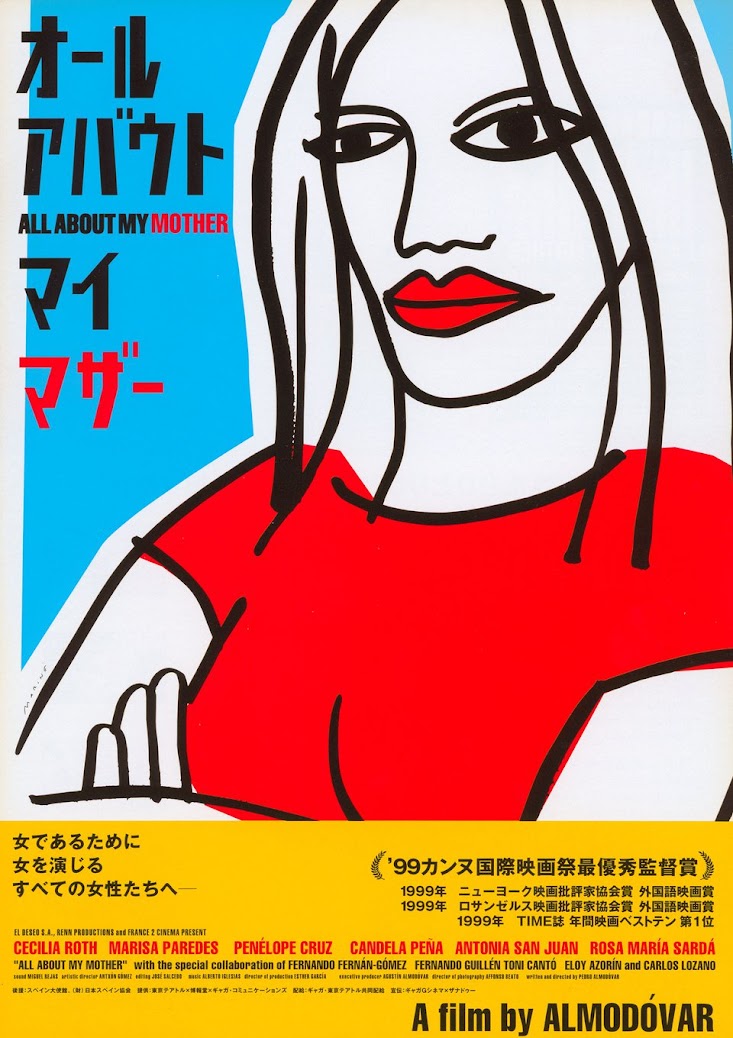

All About My Mother (1999)

In the eleven years between Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and 1999’s All About My Mother, Almodóvar continued to make films that were critical and commercial hits, including Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990), High Heels (1991), and The Flower of My Secret (1993). All About My Mother is his best known film from the 1990s however, and opened the 1999 Cannes Film Festival, where Almodóvar won Best Director. The awards kept coming for the film, which explored themes of sisterhood and family, and earned Almodóvar his first Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, as well as a Golden Globe, two BAFTAs, and six Goya Awards.

Pedro Almodovar's films are a struggle between real and fake heartbreak--between tragedy and soap opera. They're usually funny, too, which increases the tension. You don't know where to position yourself while you're watching a film like "All About My Mother," and that's part of the appeal: Do you take it seriously, like the characters do, or do you notice the bright colors and flashy art decoration, the cheerful homages to Tennessee Williams and "All About Eve" (1950) and see it as a parody? Even Almodovar's camera sometimes doesn't know where to stand: When the heroine's son writes in his journal, the camera looks at his pen from the point of view of the paper.

"All About My Mother" is one of the best films of the Spanish director, whose films present a Tennessee Williams sensibility in the visual style of a 1950s Universal-International tearjerker.Bette Davis isn't offscreen at all: Almodovar's heroines seem to be playing her. Self-parody is part of Almodovar's approach, but "All About My Mother" is also sincere and heartfelt; though two of its characters are transvestite hookers, one is a pregnant nun and two more are battling lesbians, this is a film that paradoxically expresses family values.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/all-about-my-mother-1999

Talk to Her (2002)

Talk to Her received nearly universal critical acclaim when it was released, employing unconventional cinematic techniques for mainstream films like modern dance and silent filmmaking. The film tells the story of two men who bond while taking care of a comatose woman they both love. Almodóvar won an Academy Award for Best Screenplay and was nominated for Best Director, cementing his status as not just an internationally respected filmmaker but one of the best in the industry.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/talk-to-her-2002

Bad Education (2004)

Starring Gael García Bernal and Fele Martínez, Bad Education was a drama about child sexual abuse and mixed identities, and employs unconventional storytelling structure in its screenplay. The film opened at the 57th Cannes Film Festival and.

MORE ABOUT FILM

So there's 153 words right there, and my guess is, you're thinking the hell with it, just tell us what it's about and if it's any good. Your instincts are sound. Pedro Almodovar's new movie is like an ingenious toy that is a joy to behold, until you take it apart to see what makes it work, and then it never works again. While you're watching it, you don't realize how confused you are, because it either makes sense from moment to moment or, when it doesn't, you're distracted by the sex. Life is like that.

The story, which I will not describe, involves a young movie director named Enrique (Fele Martinez) who is visited one day by Ignacio (Gael Garcia Bernal). Ignacio has written a story he wants Enrique to read. Enrique would ordinarily not be interested, but he learns that his visitor is the Ignacio – the boy who was his first adolescent love, back in school, and that the story is set in their school days and involves Ignacio being sexually abused by a priest at the school.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/bad-education-2004

Volver (2006)

Volver was a very personal film for Almodóvar, who used elements from his own childhood to craft a story about three generations of women as they deal with sexual abuse, grief, secrets, and death. The film was anchored by a powerful performance by Penélope Cruz, who earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, the first Spanish actress to do so in that category.

In Pedro Almodovar's enchanting, gentle, transgressive "Volver," a deceased matriarch named Irene (Carmen Maura) has moved in with her sister Paula (Chus Lampleave), who is growing senile and appreciates some help around the house, especially with the baking. They live, or whatever you'd call it, in a Spanish town where the men die young, and the women spend weekends cheerfully polishing and tending their graves, just as if they were keeping house for them. In exemplary classic style, Almodovar uses a right-to-left tracking shot to show this housekeeping carrying us back into the past, and then a subtle, centered zoom to establish the past as part of the present.

Almodovar is above all a director who loves women -- young, old, professional, amateur, mothers, daughters, granddaughters, dead, alive. Here his cheerful plot combines life after death with the concealment of murder, success in the restaurant business, the launching of daughters and with completely serendipitous solutions to (almost) everyone's problems. He also achieves a vivid portrait of life in a village not unlike the one where he was born.

"Volver" is Spanish for "to return," I am informed. The film reminds me of Fellini's "Amarcord," also a fanciful revisit to childhood which translates as "I remember." What the directors are doing, I think, is paying tribute to the women who raised them -- their conversations, conspiracies, ambitions, compromises and feeling for romance. (What Fellini does more closely resembles revenge.) These characters seem to get along so easily that even the introduction of a "dead" character can be taken in stride.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/volver-2006

Broken Embraces (2009)

Pedro Almodovar loves the movies with lust and abandon and the skill of an experienced lover. "Broken Embraces" is a voluptuary of a film, drunk on primary colors, caressing Penelope Cruz, using the devices of a Hitchcock to distract us with surfaces while the sinister uncoils beneath. As it ravished me, I longed for a freeze frame to allow me to savor a shot.

The movie confesses its obsession upfront. It is about seeing. A blind man asks a woman to describe herself. Since we can see her perfectly well, one purpose of this scene is to allow us to listen to her. How to describe the body, the hair, the eyes?

Harry Caine is the name Mateo Blanco takes after being blinded in an automobile accident.

Mention must be made of red. Almodovar, who always favors bright primary colors, drenches this film in red: In the clothing, the decor, the lipstick, the artwork, the furnishings -- everywhere he can. Red, the color of passion and blood. Never has he made a film more visually pulsating, and Almodovar is not shy.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/broken-embraces-2009

The Skin I Live In (2011)

The Skin I Live In was Almodóvar’s first foray into psychological horror, and is loosely based on a French novel by Thierry Jonquet. The film stars Antonio Banderas as a plastic surgeon haunted by tragedy who is obsessed with creating burn-proof skin, and ends up keeping a prisoner in his mansion to achieve this. The film reunited Banderas with Almodóvar for the first time since Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and employs a variety of cinematographic and editing techniques inspired by genre filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock, Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, and David Cronenberg.

With a Pedro Almodovar film, we expect voluptuous sexual perversion, devious plot twists, a snaky interweaving of past and present, all painted on a canvas of bright colors with bold art and clothing. His latest film, "The Skin I Live In," does not disappoint. Though I usually take pleasure in Almodovar's sexy darkness, this film induces queasiness.

What it provides is a glossy, smooth, luxurious version of the sorts of unspeakable things that occupied classified classic horror films involving mad scientists, body parts, twisted revenge, personal captives and hidden revenge. Usually such films are stylistically elevated enough that there's an irony involved, a camp humor.

It looks so silky. Few directors have used colors, especially red, as joyfully as Almodovar. Every scene vibrates. There is passion, but not chemistry; although we believe Vera actually does hope to seduce the doctor, his feelings for her seem psychopathic, not sexual. He wants to prove something. The full depth of his depravity is revealed in the unexpected final sequence, when we discover that Robert's emotional engine is fueled not by lust, jealousy or anger, but by a need to treat others as his scientific playthings.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-skin-i-live-in-2011

Pain and Glory (2019)

Almodóvar’s second last film was released and debuted at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, where it competed for the Palme d’Or. Pain and Glory tells the story of a film director whose career has peaked, and again stars Antonio Banderas, who won the Best Actor award at Cannes for his work. The film was unsurprisingly a critical hit, and became the highest-grossing Spanish film of the year.

MORE ABOUT FILM

There’s a tender, heartbreaking scene in Pedro Almodovar’s excellent “Pain and Glory,” in which one character asks another if the pain he caused him derailed his art. The other, a famous director who knows a thing or two about physical and emotional pain, scoffs at the idea. After all, art is one of the few professions not derailed by pain. Some of the best artists have worked their pain into their craft in ways that other jobs simply don’t allow. Pain doesn’t derail an artist’s career; it shapes it. And Almodovar’s film captures the way life is reflected in art in ways that only a master filmmaker could possibly even attempt. It’s a deeply personal and very moving film, anchored by the best work of Antonio Banderas’ career.

There is, of course, a long history of great filmmakers coming to terms with their own history and mortality through storytelling. “Pain and Glory” has been compared to Federico Fellini’s “8 ½” for exactly that reason. Almodovar has never shied away from telling his own stories, particularly about the women in his life, but there’s a poignancy to the way he approaches it here that he hasn’t really reached before. It’s largely due to how he places himself in the center of the story, not as an observer or cinematic memory but as the protagonist. He’s asking questions about the nature of life and art that filmmakers have certainly asked before, but there’s a grace here that’s rare, even for him. It’s a delicate, complex film, lacking in some of the visual whimsy of his best work, but as grounded in character as anything he’s done.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/pain-and-glory-2019

Parallel Mothers (2021)

That magical connection between Pedro Almodóvar and Penelope Cruz continues to grow stronger and burn brighter with “Parallel Mothers,” their eighth film together over the past quarter century.

.jpg)