Italian neorealism was a major and highly influential movement in film history, marking a conscious move away from Hollywood-style filmmaking and focusing on realistic characters and stories.

"Reality is there. Why manipulate it?" — Roberto Rossellini

Ossessione (1943)

In retrospect, the appearance of Visconti’s Ossessione (Obsession, 1943) made it clear that something original was brewing within Italian cinema. Assisted by a number of young Italian intellectuals associated with the review Cinema, Visconti took Cain’s 'hard-boiled' novel (without paying for the rights) and turned the crisp, first-person narrative voice of the American work into a more omniscient, objective camera style, as obsessed with highly formal compositions as Visconti’s protagonists are by their violent passions. Visconti reveals an Italy that includes not only the picturesque and the beautiful but also the tawdry, the ordinary, and the insignificant. Simple gestures, glances, and the absence of any dramatic action characterize the most famous sequence in the film: world-weary Giovanna (Clara Calamai) enters her squalid kitchen, takes a bowl of pasta, and begins to eat, reading the newspaper, but falls asleep from exhaustion. Postwar critics praised neorealist cinema for respecting the duration of real time in such scenes. Equally original in the film is Visconti’s deflation of the 'new' man that Italian Fascism had promised to produce. Even though the film’s protagonist, Gino, is played by Fascist Italy’s matinee idol, Massimo Girotti (1918–2003), his role in the film is resolutely nonheroic, and he has implicit homosexual leanings as well. Even Visconti’s patron and friend Vittorio Mussolini rejected such a portrayal of Italian life. Interestingly enough, Vittorio’s father, Benito Mussolini, had screened the film and did not find it objectionable.

Roberto Rossellini's War Trilogy

Though Obsession announced a new era in Italian filmmaking, at the time very few people saw the film, andfew realized that the aristocratic young director would have such a stellar career. It was the international success of Rossellini’s

Roma, città aperta (Rome, Open City, 1945), which so accurately reflected the moral and psychological atmosphere of the immediate postwar period, that alerted the world to the advent of Italian neorealism. With a daring combination of styles and moods, Rossellini captured the tension and the tragedy of Italian life under German occupation and the partisan struggle out of which the new Italian republic was subsequently born. Rome, Open City, however, is far from a programmatic attempt at cinematic realism. Rossellini relied on dramatic actors rather than nonprofessionals.

He constructed a number of studio sets (particularly the Gestapo headquarters where the most dramatic scenes in the film take place) and thus did not slavishly follow the neorealist trend of shooting films in the streets of Rome. Moreover, his plot was a melodrama in which good and evil were so clear-cut that few viewers today would identify it as realism. Even its lighting in key sequences (such as the famous torture scene) follows expressionist or American film noir conventions. Rossellini aims to provoke an emotional rather than an intellectual response, with a melodramatic account of Italian resistance to Nazi oppression. In particular, the children present at the end of the film to witness the execution of partisan priest Don Pietro (Aldo Fabrizi) point to renewed hope for what Rossellini’s protagonists call a new springtime of democracy and freedom in Italy.

Paisà (Paisan, 1946) reflects to a far greater extent the conventions of the newsreel documentary, tracing in six separate episodes the Allied invasion of Italy and its slow process through the peninsula. Far more than Rome, Open City, Paisan seemed to offer an entirely novel approach to film realism; in fact, when future young directors would cite Rossellini as their inspiration, they would almost always refer to Paisan. Its grainy film, the awkward acting of its nonprofessional protagonists, its authoritative voice-over narration, and the immediacy of its subject matter—all features associated with newsreels—do not completely describe the aesthetic quality of the work. Rossellini aims not at a merely realistic documentary of the Allied invasion and Italian suffering. His subject is a deeper philosophical theme, employing a bare minimum of aesthetic resources to follow the encounter of two cultures, resulting in initial misunderstanding but eventual brotherhood.

The third part of Rossellini’s war trilogy, Germania anno zero (Germany Year Zero, 1948), shifts the director’s attention from war-torn Italy to the disastrous effects of the war on Germany. It was shot among the debris of the ruins of Hitler’s Berlin before reconstruction. The director’s analysis of the aftereffects of Hitler’s indoctrination of a young German boy, who eventually commits suicide, reflects Rossellini’s ability to empathize with human suffering, even among ex-Nazis. Immediately noticeable and an aesthetic attributed to neorealism is the film’s atmosphere. Berlin is entirely bombed out with the family even living in a tenement that is bombed out. Long shots are utilized dwarfing the already small child to proportions that are nothing but metaphoric. Filmed in 1947, Rossellini depicted Berlin as it was objectively, never pointing a finger. Instead he presents an objective film that challenges the viewer to reveal their own sentiments toward Nazis and the German people.

Rome, Open City (1945)

Aldo Fabrizi and Anna Magnani and it was they who helped push the project through a variety of difficulties. Rome had of course been liberated by time shooting began, but conditions remained challenging to say the least, with Rossellini frequently running out of funds and resorting to using pieces of discarded film stock. Its guerrilla-style production notwithstanding, Rome, Open City stands as a crucially important picture in the development of neorealism. It led to several more films that – if not aesthetically homogenous – were united by a way of looking at the world.

Sciuscia (1946)

Vittorio De Sica's Sciuscià (Shoeshine, 1946) begins outside Rome, in a kind of idyll of the countryside. Two shoeshine boys set aside what they've earned to buy a horse. Back in the narrow and unforgiving streets of Rome, they're roped into a blackmarket deal that goes sour. Nabbed by the authorities, they're sent to a juvenile prison, their friendship strained nearly to breaking. After an escape, one of them accidentally dies, his death blamed on his friend. De Sica kept his exposition short, detailing the boys' existences through carefully composed scenes such as their neighboring prison cells, each one headed for a different fate. Opening and closing with the horse, De Sica shows the freedom that's denied these two boys.

Compared to the daring experimentalism and use of nonprofessionals in Paisan, De Sica’s neorealist works seem more traditional and closer to Hollywood narratives. Yet, De Sica uses nonprofessionals—particularly children—in both Shoeshine and The Bicycle Thieves even more brilliantly than Rossellini. In contrast to Rossellini’s dramatic editing techniques, which owe something to the lessons Rossellini learned from making documentaries and studying the Russian masters during the Fascist period, De Sica’s camera style favored the kind of deepfocus photography normally associated with Jean Renoir and Orson Welles. Shoeshine offers an ironic commentary on the hopeful ending of Rome, Open City, for its children (unlike Rossellini’s) dramatize the tragedy of childish innocence corrupted by the world of adults, the continuation of a theme De Sica began in one of his best films produced before the end of the war, I bambini ci guardano (The Children Are Watching Us, 1943). The moving performances De Sica obtains from his nonprofessional child actors in Shoeshinearise from what the director called being 'faithful to the character': De Sica believed that ordinary people could do a better job of portraying ordinary people than actors could ever do.

La terra trema: Episodio del mare (1948)

"With his film Ossessione (Obsession, 1943), Luchino Visconti put into practice the realist theories of the Cinema group trained in the Italian professional cinema of the late 1930s and early 1940s. During the war Visconti was an active participant in the Resistance and was eventually captured and imprisoned in Rome by the Nazis, who planned to execute him. He managed to escape from prison just before the American Fifth Army entered Rome in 1944. In 1946, Visconti contributed to the multi-director documentary recreation film about the Resistance, Giorni di gloria (Days of Glory, 1945).

After the war, Visconti returned to theater productions in Rome. At the same time, Visconti’s interests continued to focus on two key figures who were to influence his next film, La terra trema: Episodio del mare (The Earth Trembles): novelist Giovanni Verga and the Communist theorist Antonio Gramsci. In 1948, Visconti turned his attention to the problems of Italy’s rural poor with The Earth Trembles, an adaptation of Verga’s novel in the verismo style, I Malavoglia (The House by the Meddlar Tree). Visconti originally intended to make a film trilogy about Sicily based on Verga’s novels but only completed The Earth Trembles, an epic-length film set in the Sicilian coastal village of Aci Trezza about a young fisherman Antonio Malavoglia who tries to raise his family out of poverty by fighting the exploitative owners of the village fishing boats. Antonio decides to take out a loan with the family house as collateral in order to buy his own boat.

But the project ends in failure because Antonio is unable to enlist the support of the other fishermen in Aci Trezza.

Visconti’s film is a faithful adaptation of Verga’s novel and is close to Verga’s realistic portrayal of the Sicilian poor, showing their passions, superstitions, and stoic nobility, which often involves a passive acceptance of fate. Visconti, influenced by Verga’s attempt to accurately reproduce the speech of the Sicilian peasants, employed an entirely nonprofessional cast speaking their own Sicilian dialect. Incidentally the language used by actors is different enough from standard Italian that when the film was released in Italy, occasional voice-over commentary by Visconti was added to help non-Sicilians follow the story. Visconti’s film makes extensive use of close-ups with depictions of the day-to-day life of its characters. Visconti’s pacing in the film anticipated the art cinema style with less emphasis on action and more emphasis on character development. The film has many long sequences that may at first viewing seem unnecessary for the development of the plot, but that are actually crucial to Visconti’s study of the daily life in Aci Trezza. The film’s patient depictions of the daily habits of the fishermen and their families recall the detached scientific tone of anthropological or wildlife documentaries. Following the ideas of Communist theorist Antonio Gramsci, Visconti’s film concentrates on a rural rather than an industrial situation, and pays close attention to the regional question by emphasizing Sicilian mannerisms and speech. The Earth Trembles is a convincing portrayal of a social struggle that fails to produce significant change. Nevertheless, at the end of the film it is evident that despite his defeat, the main character, Antonio, is still determined to overcome the exploitation in his village. In practical terms, the film was one of the first box office disappointments of the neorealist period".

Germany Year Zero (1948)

In his short essay on Germany Year Zero, director Gianni Amelio (Blow to the Heart, The Stolen Children) picks up on critic José Luis Guarner’s observation that rather than a war picture, Rossellini’s film is actually closer to horror. Coming after Rome, Open City and Paisà, the film tells of Edmund (Edmund Meschke), a 12-year-old boy having to prematurely shoulder adult responsibility in a devastated post-war Berlin. “The adults around little Edmund aren’t vampires but zombies” writes Amelio, “they move among the rubble of their city without past or future, poised between life and death.”

In the months before he made Germany Year Zero, Rossellini lost his nine-year-old son Romano, a tragedy that undoubtedly contributed to the film’s air of unrelenting pessimism. Its final passage, with an isolated Edmund walking across the skeletal landscape of Berlin, remains one of the most extraordinary sequences ever committed to film.

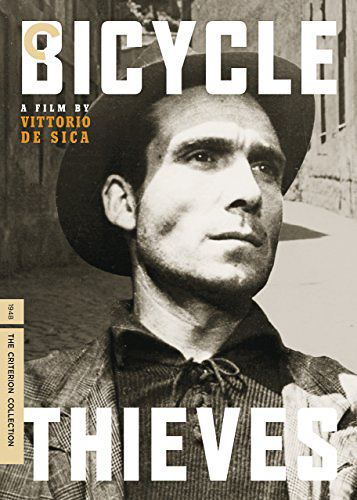

Ladri di biciclette (1948)

De Sica’s faith in nonprofessional actors was more than justified in his masterpiece, Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thieves, 1948), the leading roles of father and son occupied by two nonprofessionals. (David O. Selznick was willing to back the film, but only with Cary Grant as lead, an offer De Sica fortunately had the confidence to refuse.) When the bicycle he needs to do his job is stolen, the young father and son scour Rome to find it; the father is finally driven to steal a ride of his own. The Bicycle Thieves also employs location shooting and the social themes of unemployment and the effects of the war on the postwar economy. De Sica’s faith in nonprofessional actors was more than justified in his masterpiece, Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thieves, 1948), the leading roles of father and son occupied by two nonprofessionals. (David O. Selznick was willing to back the film, but only with Cary Grant as lead, an offer De Sica fortunately had the confidence to refuse.) When the bicycle he needs to do his job is stolen, the young father and son scour Rome to find it; the father is finally driven to steal a ride of his own. The Bicycle Thieves also employs location shooting and the social themes of unemployment and the effects of the war on the postwar economy.

The performances of Lamberto Maggiorani as Antonio Ricci, the unemployed father who needs a bicycle in order to make a living hanging posters on city walls, and Enzo Staiola as Bruno, his faithful son, rest upon a plot with a mythic structure - a quest. Their search for a stolen bicycle - its brand is ironically Fides ('Faith') - suggests the film is not merely a political film denouncing a particular socioeconomic system. Social reform may change a world in which the loss of a mere bicycle spells economic disaster, but no amount of social engineering or even revolution will alter solitude, loneliness, and individual alienation.

De Sica orchestrated the film carefully, shooting some scenes with multiple cameras and drawing attention to its existence as fiction, not a documentary. Bazin termed it the "only valid Communist film of the whole past decade" and the film was often seen as simply a criticism of working conditions in Italy at the time, when unemployment stood at 25 percent. But unlike the clearcut moralizing of Rossellini's films, De Sica's works focus on a humanist sense of individual and mass. Bicycle Thieves has a mythic feel, the father ultimately forced into thievery, each moral quandary no sooner solved than De Sica poses yet another, the father sympathetic but flawed.

Miracolo a Milano (1951)

De Sica’s Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan, 1951) abandons many of the conventions of neorealist 'realism.' Not only does the film rely upon veterans of the legitimate theater for its cast, but De Sica also employs many special effects not generally associated with neorealism’s pseudodocumentary style: superimposed images for magical effects, process shots, reverse action, surrealistic sets, the abandonment of normal notions of chronological time, and the rejection of the usual cause-and-effect relationships typical of the 'real' world.

De Sica’s scriptwriter, once made a famous pronouncement that "the true function of the cinema is not to tell fables" (a view that became associated with Italian neorealism and that tended to obscure the very real fables that this cinema invented), Miracle in Milan is, in fact, a fable that begins with the traditional opening line, "Once upon a time . . ." and revolves around a comic parable about the rich and the poor. The result is a parody of Marxist concepts of class struggle. De Sica and Zavattini show us poor people who are just as selfish, egotistical, and uncaring as some wealthy members of society once the poor gain power, money, and influence. At the conclusion of the film, the poor mount their broomsticks and fly off over the Cathedral of Milan in search of a place where justice prevails and common humanity is a way of life. Miracle in Milan stretches the notion of what constitutes a neorealist film to the very limits.

Bellissima (1951)

Italian audiences hardly embraced these new films. To be shown their country in such stark terms made the majority very unhappy. It even became part of the law: the Andreotti Law (1949), named for its author Giullio Andreotti, offered subsidies for those who followed the neo-realist style in a manner "suitable... to the best interests of Italy," but with the proviso that they avoid the blemishes on Italian life. Legislation had little immediate effect on what was made, though the stories began to reflect the scramble for work and stability that defined this period. Visconti's terrific Bellissima (1951) centers on a daughter and fanatic stage-mamma, the inimitable Magnani, eager to get her modestly talented daughter a spot in a movie.

To her husband's dismay, she squeezes every extra penny into lessons and cosmetic improvements for the little girl. Ultimately, the mother all but puts herself on the market to get the recognition she's convinced will make life worth living. Set in a working-class Roman neighborhood,Bellissima gives rare insight into how provincial big-city life could be, each neighborhood a virtual small town, the neighbors sometimes helpful, often petty and jealous of any advantage. Though not traditionally considered a neo-realist film, Bellissimadid focus on people's lives in the wake of war, the sense of wanting to better oneself and the struggle to find a way out of the grind of poverty. It becomes yet more poignant in this context.

Umberto D. (1952)

The sense of Rome as a small town is especially acute in Umberto D. (1952), which was De Sica's favorite film and is in many ways the masterpiece of neo-realism, an overall superb piece of work. The crisis-filled days of a pensioner, Umberto Domenico Ferrari (Carlo Battisti), and the complications of his relationship with his dog and a young maid in his apartment building become a study in the difficult drama that constitutes an ordinary life. As played by a dignified nonprofessional - a professor, who, in the event, was often subsequently taken for his character on the street - Umberto D. is stodgy, fussy, irritating and curiously sympathetic. Unlike other films of the era, this was shot nearly entirely in the Cinécitta studios.

The indignities of the family-less and indigent old-age are laid out with sensitivity but not sentimentality. Umberto is vulnerable and all but invisible, barely distinguishing himself in a crowd of protesting pensioners, desperately trying to maintain his independence and self-respect. There is no real plot other than the minuscule and life-shaping crises of late-life impoverishment. Even the end strikes a melancholy note of ambiguity.Umberto is upright, neat, exact, and the cut of his clothes shows that he was once respectable. Now he is a retired civil servant on a fixed income that is not enough to support him, not even in his simple furnished room, not even if he skips meals. He and his dog are faced with eviction by a greedy landlady who would rather rent his room by the afternoon to shame-faced couples.

Vittorio De Sica's "Umberto D" (1952) is the story of the old man's struggle to keep from falling from poverty into shame. It may be the best of the Italian neorealist films--the one that is most simply itself, and does not reach for its effects or strain to make its message clear. Even its scenes involving Umberto's little dog are told without the sentimentality that pets often bring into stories. Umberto loves the dog and the dog loves him because that is the nature of the bond between dogs and men, and both try to live up to their side of the contract.

La strada (1954)

Within a few years of moving to Rome from his native Rimini, Fellini met Roberto Rossellini, who invited him to collaborate on the screenplay for Rome, Open City. Fellini then served as Rossellini’s assistant director on Paisà a year later. “It was a very important experience for me”, he said in an interview with Costanzo Costantini, “Rossellini was the originator of open-air cinema, working in the midst of ordinary people in the most unpredictable circumstances. It was by accompanying him as he shot Paisà that I discovered Italy. From him I derived the conception of film as a journey, adventure, odyssey.”

When Fellini became a director in his own right in the early 1950s, his work clearly showed links with (Rossellinian) neorealism while possessing an oneiric quality all of his own. In 1954’s La strada, Fellini’s wife Giulietta Masina plays Gelsomina, a young woman whose impoverished mother sells her to travelling circus strongman Zampanò .

(Anthony Quinn

). An intensely bittersweet fable, La strada proved to be Fellini’s international breakthrough, winning the inaugural Academy Award for best foreign film in 1956.The movie is the bridge between the postwar Italian neorealism which shaped Fellini, and the fanciful autobiographical extravaganzas which followed. It is fashionable to call it his best work - to see the rest of his career as a long slide into self-indulgence. I don't see it that way. I think "La Strada" is part of a process of discovery that led to the masterpieces "La Dolce Vita" (1960), "8 1/2" (1963) and "Amarcord" (1974), and to the bewitching films he made in between, like "Juliet of the Spirits" (1965) and "Fellini's Roma" (1972). "La Strada" is the first film that can be called entirely "Felliniesque." It is being re-released, in a restored print presented by Martin Scorsese, at a poignant moment: Fellini received an honorary Oscar at the 1993 Academy Awards, with his wife Giulietta Masina applauding tearfully in the front row. Since then, both have died.When Fellini died, the critic Stanley Kauffmann wrote an appreciation in The New Republic that ended with the words: "During his lifetime, many fine filmmakers blessed us with their art, but he was the only one who made us feel that each of his films, whatever its merits, was a present from a friend." In the words of a film about him, "Ciao, Federico."

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/la-strada-1994

ITALIAN NEOREALISM CINEMA >>>

ITALIAN NEO-REALISM CINEMA-MAJOR DIRECTORS >>>

Top 26 Best Italian Neorealism Films IMDB>>>

.jpg)